130223

AMERICAN CLIMATE POLITICS: A GUIDE (PART ONE)

Past, present, and future

___________________________________________________________________________

DIMENSIONS OF POLITICS DIMENSIONS OF POSTS

Sectors: Energy, environment, economy Importance: *****

Level: National Scope: USA only

Period: Short, middle, and long runs Process: Policy politics

MAIN TOPIC: Climate Treatment: Commentary. Background.

____________________________________________________________________________

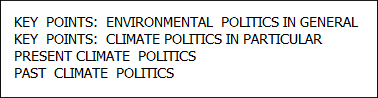

KEY POINTS: ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS IN GENERAL 1

Relevant policy domains 1.1

Evolving policy purposes 1.2

Postwar regulatory regime 1.3

KEY POINTS: CLIMATE POLITICS IN PARTICULAR 2

Recent dynamics 2.1

Current partisanship 2.2

Proposed measures 2.3

PRESENT CLIMATE POLITICS 3

2009-2010 3.1

2011-2012 3.2

2013-2014 3.3

PAST CLIMATE POLITICS 4

Nixon-Carter 4.1

Reagan-Bush 4.2

Clinton-Bush 4.3

____________________________________________________________________________

In early 2013, CLIMATE is again on Washington’s policy agenda. This Post focuses on the current (re) emergence of CLIMATE as a focus within the complex “EEE” policy domain where ENVIRONMENT, ENERGY, and ECONOMY overlap. A second Post will overview EEE politics more generally. All of this amounts to a great deal of material so, as usual, readers are invited to proceed only as far as their interests take them. We begin by summarizing Key Points, first environmental politics in general, then climate politics in particular.

KEY POINTS: ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS IN GENERAL 1

Relevant policy domains 1.1

Climate politics falls within the overlap of many policy domains, particularly ENVIRONMENT, ENERGY, and ECONOMY (EEE). Others are industry and agriculture, domestic commerce and foreign trade, defense and diplomacy. Thus also SECURITY, both external and internal.

Climate is partly an ENVIRONMENTAL issue. Some traditional environmental analytics apply to it. Nevertheless, squarely addressing climate change requires superceding traditional American environmental ideology and organization.

Controlling climate requires switching away from carbon ENERGY. American politicians would prefer to do that through positive subsidies and benefits, but also use mandates that impose costs on business and consumers.

The politically most feasible way to limit climate change is by promoting a “green” ECONOMY that promises “green” jobs and “green” prosperity. That is how Obama has framed the issue (much to the exasperation of some environmentalists).

For controlling the USA’s carbon emissions, a positive factor is that its Economy still needs stimulus, including through green investments. A complicating factor, in Energy, is the unexpected development of cheap natural gas.

Evolving policy purposes 1.2

Historically, the USA has managed its vast natural RESOURCES through the Interior Department, mostly to DEVELOP them, eventually also to CONSERVE them. The Interior Department still is supposed to pursue both purposes.

Early local environmentalism sought CONSERVATION of specific natural or historic AMENITIES, usually by opposing local development. This is still a main frame under which climate issues arise (e.g., local opposition to local impacts of national energy development).

Later national American environmentalism also sought MITIGATION of regional harms, particularly POLLUTION of land, water, or air. Some efforts succeeded more than others. On climate, anti-environmentalists long opposed defining carbon dioxide as a pollutant.

American environmental politics have not much addressed ADAPTATION to ongoing climate change. Recent severe weather has dramatized the need. Plausible future scenarios range from difficult through severe to catastrophic.

As often in American policy, so in climate control, subnational levels have pioneered policies for both the USA and other countries to adopt. Nevertheless, so far, American national politics has done little to prevent or mitigate climate change, even less to adapt to it.

Postwar regulatory regime 1. 3

The main current American regime for environmental regulation – controlling pollution and protecting biodiversity – was institutionalized in the early 1970s. Since then EEE politics have alternated between weakening and strengthening that regime.

Different parts of that regime have fared differently. CONTROLLING CLIMATE has come last and been weakest, blocked by strong industry opposition. Nationally, on this issue, government agencies, advocacy organizations, and public opinion remain fragmented.

PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY has fared better, despite weak public support and a weak national agency: The Fish and Wildlife Service is supervised by the Interior Department, which usually prioritizes Development over Conservation.

CONTROLLING POLLUTION has done best, benefitting from strong public support, strong national lobbying organizations, and a strong national agency (the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA).

Consequently, particularly in the EPA subdomain, businesses wanting to minimize regulation have learned to do so indirectly: by funding others’ challenges to conservationist beliefs and by quietly weakening particular regulations and their enforcement.

KEY POINTS: CLIMATE POLITICS IN PARTICULAR 2

Recent dynamics 2.1

Climate scientists began warning of climate dangers in the 1970s. Since then environmentalists have tried to raise climate issues, but with little policy success. The issue regressed under Republican administrations and even under some Democratic ones.

Recent national climate politics has been mostly INSIDE Washington: centrist elite national advocacy organizations seeking agreement on optimal policies between themselves, centrist industry leaders, and centrist politicians.

Climate control still lacks an OUTSIDE national mass movement to provide political leverage over politicians reluctant to oppose carbon-based businesses or populist conservatives. That lack allows industry and conservatives to block control.

Meanwhile, progressive states continue to experiment with regional measures but find it hard to make real progress. National action could imitate and promote subnational progress, but it could also “preempt” and constrain it.

Meanwhile, climate scientists warn that measures taken so far will not be strong enough to prevent climate catastrophe, which grows ever more imminent as American politics delays attempts at a national solution.

Current partisanship 2.2

Historically, both Republicans and Democrats strongly promoted Development. Republicans initiated Conservation around 1900 (Theodore Roosevelt). Nevertheless, most Democrats are now more Conservationist than most Republicans.

Currently, REPUBLICANS are publicly united against climate control, though some relative moderates would prefer some control. Public unity among Republican politicians helps them obstruct climate control legislation.

Currently, DEMOCRATS are publicly divided on climate: Most support control, but those from states with carbon-based industries oppose it. The electoral need to protect those Democrats cripples Democratic legislative initiatives and inhibits Obama executive action.

In his FIRST TERM, Obama did not do much about climate, though he directed some economic stimulus funds to promoting energy efficiency and energy alternatives. In early 2010 a climate control act passed the then-Democratic House but not the Democratic Senate.

In his SECOND TERM, Obama’s main way to control climate will again be through executive orders not requiring congressional approval, such as having agencies reduce harmful emissions, particularly from electrical generation that burns coal.

Proposed measures 2.3

In early 2010, a Democratic Senate failed to pass what long seemed the most promising approach to limiting climate change: CAP-AND-TRADE. This “market-based” solution was originally proposed by conservatives and accepted by some leading industries.

By late 2010, the carbon industry had mobilized conservatives against ANY form of climate control. Republicans then captured the House, so they can still block any new regulation, even if it could pass the Democratic Senate, which is unlikely.

The failure of cap-and-trade left advocates of climate control without an obvious policy to propose. Advocates remain splintered between conciliatory versus adversarial approaches to carbon businesses and between diverse national and local organizations.

“Fiscal crisis” might have permitted a different market-based approach much favored by economists: a TAX ON CARBON emissions. That now seems unlikely, given Republicans’ opposition both to environmental regulation and to any further increase in taxes.

A third market-based approach is CAP-AND-DIVIDEND. Government would auction carbon quotas to industry and distribute the resulting revenues equally to all Americans. That might help create popular support for regulating carbon emissions.

______________________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

We turn now to sketching the dynamics of American environmental politics and the difficult emergence of a focus within them on climate. We treat first developments during the Obama administration (2009-present). We then show that the dynamics involved have been accumulating over the previous half century (1960s-2000s). As usual, we try to relate the best current media coverage to the best recent academic analysis. The last third of the next post (130302) will recommend readings on American environmental politics in general and climate politics in particular, summarizing some of the main arguments of the best books on climate.

This Post relies particularly on Judith Layzer 2012Open for business: Conservatives’ opposition to environment regulation. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 499 pages. This important analytical history shows how, across the past forty years, conservatives have been highly successful at blocking measures to control climate. They were less successful at limiting protection of biodiversity and least successful at rolling back controls on pollution.

PRESENT CLIMATE POLITICS (UNDER OBAMA) 3

This section sketches the state of political play on climate issues under Obama (2009-2013), particularly at the beginning of his second term (2013-2017). We note the main current partisan positions, the main current policy proposals, and the main institutions that will process them. (For a brief academic treatment of the early Obama period see Layzer 350-360.)

As noted toward the end of Key Points (under 2.3), the most promising policy for reducing carbon emissions long appeared to be “cap-and-trade”: putting a cap on carbon emissions while allowing companies to trade permits to pollute. This is a market-based approach that worked well from1990 to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide in order to reduce acid rain. As a market-based approach, it appealed to economic conservatives such as the American Enterprise Institute. In 2008 it was endorsed by the moderate Republican candidate for president John McCain. In 2010 centrist legislators attempted to use cap-and-trade to limit emissions of the greenhouse gasses that cause climate change. The then-Democratic House passed a bill but the Democratic Senate did not. Environmentalists despaired, but US emissions fell anyway, mostly because economic recession has reduced economic activity and because cheap natural gas has displaced some coal in generating electricity.

Between the past two American presidential elections (2008 and 2012), both Republicans and Democrats modified their positions, Republicans much more so. To some extent these modification reflected the actual course of energy affairs since 2008: US environmental emissions went down, and US energy independence went up. But to a greater extent these modification reflected the increasing political polarization between the two parties on all issues:. Republicans moved sharply to the right, while Democrats moved a little to the left. As Judith Layzer points out, this polarization had several consequences for EEE politics. Republicans gave up trying to win environmentalists’ votes while Democrats took them for granted. Even reforms with near universal public support were stymied. Polarization undermined agencies’ ability to adapt existing practices to emerging realities. An increasingly conservative Supreme Court sided increasingly with business (Layzer 349-350).

In 2008 the Republican policy platform and Republican presidential candidate acknowledged the existence of climate change, affirmed the urgency of limiting it, and advocated using cap-and-trade to reduce carbon emissions. In contrast, in 2012 the Republican platform and candidate made virtually no mention of climate change, vehemently rejected any cap-and-trade legislation, and advocated energy independence through still more intensive exploitation of North American carbon resources. (Brad Plummer 120830 “GOP platform highlights the party’s abrupt shift on energy, climate” on Wonkblog at . All subsequent Plumer citations are at that same site.)

In 2008 the Democratic platform and candidate regarded climate change as an urgent matter and advocated legislating a cap-and-trade system, in order to drastically reduce emissions and to strongly encourage industry investment in alternative energy. In 2012 Democrats downplayed climate issues in favor of economic issues and downsized their policy proposals from comprehensive legislation to executive measures. In 2012 Democrats remained optimistic about prospective contributions from alternative energies, but acknowledged the surprising new contribution of oil and gas. (Brad Plumer 120904 “How Democrats have shifted on climate, energy since 2008.”)

2009-2010 3.1

As Obama approached office in late 2008, there appeared to be a window of opportunity for legislation to limit climate change (Layzer 350). The extreme anti-environmentalism of the preceding Bush administration had alarmed the largely pro-environmental American public. Even Republicans themselves appeared potentially divided on the issue, between establishment conservatives wanting to meet public expectations for some regulation of greenhouse gases and insurgent radicals opposing any government activism. Democrats divided between support of progressives for regulation and opposition from “moderates” in states with carbon-based industries. Thus passing climate legislation through a Democratic-controlled House and Senate might require some help from moderate Republicans, but still appeared feasible.

Nevertheless, during his first term, Obama had to deal mostly with other issues. He approached Environment and Energy mostly through the Economy, strongly promoting new “green” industries as sources of future green jobs. (For a critique, see Joe Romm 121104 “The sounds of silence: Team Obama launched the inane strategy of downplaying climate change back in March 2009" at ) Upon taking office, Obama took strong EEE stands. He declared that Economic recovery required a drastic shift in Energy supply. His first budget increased spending by the Energy department on energy efficiency and energy alternatives, and it anticipated a large increase in revenue from cap-and-trade. (Layzer 353).

Nevertheless, Obama’s initial appointments and instructions to environmental agencies appeared ambivalent. At the EPA, a strong environmentalist moved quickly to tighten regulation of pollution. However, at the Interior Department (supervising the Fish and Wildlife Service), a moderate did NOT tighten lax Bush protection of biodiversity, did NOT speed up the listing of new species for protection, and decided NOT to use the Endangered Species Act to combat climate change. (Layzer 351-353).

Moreover, the apparent window for new legislation quickly began closing. In 2009, Obama’s necessary activism to combat the Great Recession quickly re-mobilized populist conservatives in opposition to regulation. Elite conservative propagandists derided “cap-and-trade” as “cap-and-tax” and attacked the credibility of climate science. To gain influence over potential cap-and-trade legislation, some leading companies claimed to endorse it, but meanwhile their trade associations campaigned fiercely against it. Recession shifted public priorities from environment to jobs. (Layzer 354-356.)

All of this dimmed the prospect for cap-and-trade legislation. In June 2009, with strong Democratic leadership (Pelosi and Obama), the House passed a comprehensive bill on energy and climate change. However, despite concessions to energy interests, the Senate was unable to process a similar bill. By mid-2010, facing increasing senatorial ambivalence and a still-weakening economy, Democratic leadership (Reid and Obama) gave up. (On the 2010 failure, see Ryan Lizza 101011 “As the world burns: How the Senate and the White House missed their best chance to deal with climate change” at . For a detailed critique of environmentalists’ strategies, see Theda Skocpol 2013 “Naming the issue: What it will take to counter extremism and engage Americans in the fight against global warming.” Also Petra Bartosiewicz and Marissa Miley 2013 "The too polite revolution: Why the recent campaign to pass comprehensive climate legislation in the United States failed." Both at .)

2011-2012 3.2

The 2010 elections gave Republicans the House and weakened Democrats in the Senate. Obama gave conservatives a concession by ordering executive agencies to review how to reduce unnecessary burdens of regulation. That did not placate House conservatives, who redoubled their attacks on EPA regulation as “too much, too fast” and costing jobs. The House tried – mostly unsuccessfully – to cut the budgets of relevant agencies, strip EPA of its authority to regulate carbon dioxide, and to reduce government research on energy and climate. Obama continued to promote clean energy, but gave conservatives another concession by including nuclear energy, “clean coal,” and natural gas as “renewables” qualifying for government support. Nevertheless, Republicans still denounced the bill as “job-slashing overreach.” Meanwhile EPA continued trying to strengthen control of air pollution, failing on ozone but succeeding on mercury. (Layzer 358-360)

The 2012 presidential campaign did not go deeply into EEE issues and avoided debating climate change altogether (Brad Plumer 121018 “How climate change disappeared from the debates.”) Not only did the presidential debates avoid asking what to do about climate change, they also ignored what to do about other current developments such as Arctic melting, North America’s becoming a major energy producer, and the effect of biofuels in driving up global food prices. The debates also did not discuss what kinds of energy infrastructure the USA should be exporting to the rest of the world. (Brad Plumer 121022 “Five energy topics that won’t come up in tonight’s foreign policy debate – but should.”)

Objective practical and political circumstances drove the two 2012 presidential candidates toward similar positions (Clifford Krauss 121023 “Bigger than either of them?” in the Business section under Energy-Environment at ). Nevertheless, debates between the candidates’ academic surrogates revealed some differences (Brad Plumer 121024 “Want a more substantive Obama-Romney debate on energy and climate? Read this”). These positions are worth noting because, even though the election is over, they remain the positions of the two parties. Romney would have done little about climate change. He would have had the government fund basic research on energy technologies (as it did on shale), but not sponsor particular companies. Romney criticized fuel-efficiency standards, believing that “the market” would produce the kinds of vehicles that consumers want. Romney promised energy independence, but probably understood that it would not make Americans immune to global energy prices.

In accepting his re-election, Obama finally remarked that “We want our kids to grow up in an America... that isn’t threatened by the destructive power of a warming planet.” Obama’s reelection guaranteed the continuation of the executive initiatives he took on energy during his first term and set the stage for followup executive initiatives during his second term. Nevertheless, major new progress would require major new legislation, which evidently Obama thinks it counter-productive for him to propose, unless Republicans are willing to negotiate. (Brad Plumer 121107 “Obama finally talks climate change. Now what will he do about it?”) For an argument that “going big” on climate change requires building coalitions between those who want to slow climate change and those who want to develop North American oil and gas, see Michael Levi 121107 “Two paths forward on climate change” and 121109 “Two paths forward on oil and gas” (at ).

2013-2014 3.3

Overall, in his second term Obama seems most likely to continue the low-key administrative approach to climate control that he took in his first term. Cumulatively, even those small actions could be significant. But some former Obama energy advisers think that eventually he will attempt bigger initiatives, perhaps major legislation, perhaps direct negotiations with electric power companies. (Darren Samuelsohn 130123 “Obama's covert plans for climate” at .)

Key players include Obama’s new chief of staff Denis McDonough, his deputy assistant for energy and climate change Heather Zichal, and his new secretary of state John Kerry, along with leaders of key government agencies, business groups, and environmental advocacy organizations. (Darren Goode 130203 “Obama’s climate team appears primed for action” at .) Meanwhile, as part of general restaffing for Obama’s second administration, discussion swirled around Obama’s rumored picks for top jobs at EPA and the Energy department. (Zack Colman 130222 “Industry, advocates await Obama’s energy team” at . Also Ben Geman 130222 “Rumored energy pick stirs fears on left” on the Energy & Environment blog ( E2Wire) at .)

Given renewed fiscal crisis and other active issues, for the moment climate matters are not at the top of the policy agenda (Amy Harder 130206 “In Washington, energy and climate issues get shoved in the closet” at ). Nevertheless, relevant bureaucratic routines continue. The EPA will issue a report acknowledging that global warming is proceeding faster than it had earlier thought, forcing EPA to address it (Ben Goad 130207 “EPA to issue climate change plan Friday ” on Regwatch at .) This spring a panel that coordinates national research on climate will release a report containing newly drastic warnings about climate changes that have already occurred and that will occur in the near future (Justin Gillis 130114 “An alarm in the offing on climate change” on the blog Green at .) A major environmental advocacy group reminded the country of its slow progress (Juliet Eilperin 130206 “U.S. could fall short of 2020 climate goal, new study says, but target remains in reach” at .)

One difficult decision that Obama faces is whether to approve a pipline extension to carry oil from Canadian tar sands to the American Gulf Coast, in part for export (not least to China). Opponents deplore both adding carbon from the tar sands to the atmosphere and the local environmental impact of the pipeline itself. Proponents declare that if Canada can’t export that oil south through the USA it will build a pipeline west to its own Pacific Coast and export the oil anyway (again not least to China). Obama will deeply disappoint environmentalists if he approves the pipeline, but open himself to criticism from Republicans if he does not. (John M. Broder+ 130217 “Obama faces risks in pipeline decision” at . Also Steven Mufson 130217 “Crowd marches to voice opposition to Keystone pipeline” at . Also Elana Schor 130215 “Are environmentalists getting it wrong on the Keystone XL pipeline?” at .)

Given the 2010 failure of cap-and-trade, in the future the most likely measures are to further REGULATE carbon and other emissions from electric power plants. During the first Obama administration, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set higher standards for future power plants. During the second Obama administration the EPA could attempt to set higher standards for existing power plants (Brad Plumer 121204 “How to cut U.S. carbon emissions by 10 percent – without Congress”).

Another possible future policy is to TAX carbon emissions (Elizabeth Kolbert 121210 “Paying for it” at ). According to conventional economics, that is the logical way to reduce carbon emissions, because increasing their cost should reduce their consumption. Unfortunately, politicians try to avoid increasing anyone’s costs. Despite this, and despite politicians’ general opposition to new taxes, a tax on carbon might have become politically feasible if, in the context of negotiations over how to solve the “fiscal crisis,” a tax on carbon had become an attractive source of revenue (Brad Plumer 120827 “Could a carbon tax help the U.S. avert the fiscal cliff?”). Republicans might have accepted a tax on carbon if it had been substituted for other kinds of taxes – on higher incomes or capital gains – that Republicans regard as impediments to economic growth. However, on 1 January 2013 Obama obtained the increase in taxes on higher incomes that he had long sought. Since then Republicans have adamantly rejected any further increase in taxes of any kind. Some Democratic might support a tax on carbon if it were accompanied by progressive fiscal measures, such as using the revenues from a regressive carbon tax to fund progressive social programs. A tax on carbon would be regressive (a bigger burden on poorer people than on richer people) because it would raise the prices of such basics as electricity and gasoline that everyone, including poor people, must use.

“Obama also has options for expanding the use of federal lands for renewables, [drafting] appliance efficiency standards and working to craft an adaptation strategy that can help vulnerable communities prepare for rising sea levels and more intense storm surges. There are policies for dealing with pollutants other than carbon dioxide, like methane and soot, which can be sped up. On the international stage, U.S. diplomats are working with other countries including China to reach a broad agreement by the end of 2015.” (Again Darren Samuelsohn 130123 “Obama's covert plans for climate” at .)

(For a listing of articles on overall policy options see Joe Romm 121111 “Real adaptation is as politically tough as mitigation, but much more expensive and less effective at reducing future misery” at )

Like all American policy politics, climate politics involves the interaction of all of America’s political institutions: legislative, executive, and judicial. Given the failure of new legislation, president Obama has turned to using executive powers already granted him by previous legislation, whose exercise does not require further congressional approval. Here the main executive organ is the EPA. However, Obama can also work through other executive agencies, addressing climate change as an aspect of finance, urban planning, environmental impacts, and management of public lands (Layzer 356) – even national defense . So far the judiciary has upheld Obama administration executive actions on EEE matters, but the result is uncertain for new suits against new actions. So we should look more closely at the actual and potential role of the judicial branch in EEE issues.

On the positive side are court rulings that support the foundational 1970 and 1990 versions of the Clean Air Act. In 2007, during the Bush administration, the Supreme Court ruled that the Act not only PERMITTED the EPA to regulate greenhouse gasses but actually REQUIRED it to do so, if the EPA found them a risk to human health. In 2009, under Obama, the EPA determined that they ARE such a risk and crafted new fuel economy standards for vehicles. In 2012 EPA proposed new limits on carbon pollution from new power plants. Dozens of states and industry groups challenged this, but a US Court of Appeals upheld EPA (Brad Plumer 120626 “EPA’s climate rules upheld in court” ).

On the negative side, it is not clear how far Supreme Court support for executive actions will extend in the future. Resources for the Future points out that the Clean Air Act envisaged that EPA would set only specific emission standards for particular power plants, not set overall energy policy for whole jurisdictions (Brad Plumer 121207 “How much can the EPA cut carbon emissions? It depends on the courts”). The Supreme Court could also decide to limit executive action on broader constitutional grounds. Its July 2012 ruling upheld most of Obama’s health reform but said the national government could NOT coerce states: that is, threaten them with withdrawal of existing health subsidies in order to compel them to expand the coverage of their Medicaid programs. Having established that principle, the Supreme Court COULD rule something similar about energy reform: the EPA regularly forces states to strengthen their regulation of emissions by threatening to withhold part of their federal highway funds, which constitute a high proportion of state transportation budgets. States that do not want to comply with new air pollution standards could sue the EPA over the matter, and the Supreme Court might agree with the states. (Brad Plumer 120727 “How the Supreme Court’s health care ruling could weaken the Clean Air Act.”)

PAST POLITICS (BEFORE OBAMA) 4

An analytical narrative of American environmental politics involves many components, particularly including effective political organization and persuasive policy narratives. Different branches of government and different levels of organization create successive layers of both general objectives and specific regulations. The regulatory regime strengthens and weakens through repeated cycles in which regulatory initiatives are followed by anti-regulatory backlash, which in turn produces environmentalist backlash, and so on. Different parts of the regime fare better than others: controlling pollution does better than protecting biodiviersity which does better than controlling environment.

(The following account summarizes Lazyer 2012. Her handling of the interplay of the components of American environmental politics is particularly systematic and incisive. She organizes her history by presidencies. Given her interest in the impact of conservative ideas, she begins chapters on each presidency by sketching the conservative ideas prevalent at the time. She then reports the interaction of president and congress on environmental policy in general. Then she treats the three subdomains of controlling pollution, preserving biodiversity, and controlling climate. She concludes each chapter with a roundup of other influences such as the judiciary and media.)

First some historical background. It took European settlers about three centuries (1600-1900) to conquer North American from its indigenous inhabitants and exploit its natural environment. For the first hundred years of the USA (roughly 1800 to 1900), the main role of the national government was to facilitate the acquisition and development of the continent’s natural resources. (The national government itself ended up owning about half of the mineral-rich Mountain West.) However, by the middle of the 1800s, American artists and elites developed an almost spiritual appreciation for the beauty of America’s diverse natural landscapes. By around 1900, settlement and industrialization were doing so much damage to those landscapes that governing elites began setting aside large tracts of land as national parks, forests, and monuments for mass public recreation. Meanwhile, ecological damage to much of the rest of the country proceeded apace.

Nixon-Carter 4.1

By the 1960s, to counter the traditional “developmentalist” narrative, a new “environmentalist” narrative emerged in which unregulated urban and industrial development threatened not only natural beauty but also human health. Given the popularity of this new environmentalism, in the early 1970s, centrist Republican president Richard Nixon worked together with a Democratic congress to pass a series of laws that, together, established an environmental “regulatory regime.”

The first of these laws was the January 1970 National Environmental Policy Act, which created a national Council on Environmental Quality to advise the president and require all agencies to consider the environment in their decisions (usually though a formal “environmental impact statement”). In the course of the 1970s, environmentalism became firmly institutionalized in national government laws and agencies. It became extensively embedded in a pro-environmental policy community of administrators and politicians, experts and advocates. That regulatory regime and its policy community remain in place today.

However, early implementation of environmental regulation quickly provoked an anti-regulatory backlash from industry and “small government” conservatives. The backlash included material support both for anti-regulatory politicians and for anti-regulatory think tanks. They produced a new anti-environmentalist narrative according to which regulation was impeding economic development and economic efficiency. That backlash forced leading politicians to combine a sometimes only apparent commitment to environmentalism with actual policy practices that often were anti-environmental. (Layzer calls this “political learning.”)

Not only Nixon but also Carter began his administration as an environmentalist but soon made substantial concessions to anti-environmental backlash. (Ford was anti-environmental throughout his short presidency.) In the course of the 1970s, as the USA encountered increasing economic difficulties, priority gradually shifted from protecting the environment to promoting the economy. Influenced by marketist economics, Carter began economic “deregulation” in several policy domains, including the environment. Meanwhile, experience with implementing environmental regulation revealed the need for some reform, accepted even by many environmentalists. (Layzer calls this “policy learning.”)

On POLLUTION, the new environmental regulatory regime began from it and was strongest in that subdomain. In July 1970, by administrative reorganization, president Nixon established an Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA was entirely devoted to conservation, not also development. By the end of the year, congress had overwhelming passed a Clean Air Act making clean air a fundamental national value, a drastic departure from previous “economism..” (34-36) However, strong pollution controls provoked the earliest and strongest backlash, leading to some weakening of regulation. During reauthorization of the Clean Air Act in 1977, Carter repelled efforts to weaken it. However, as inflation worsened, he acceded to advice from economists to reduce the cost of regulation. (68-71)

On BIODIVERSITY, in 1973 congress overwhelmingly passed an Endangered Species Act, also a sharp departure from previous economism. However, although the act was stringent, the small agency that administers it is buried deep within the large Interior department with its longstanding commitment to development. (36-37) By the late 1970s, this act too provoked conservative backlash, against the cost of protecting certain obscure species of bears, birds, and fish. Opponents argued that extinction was a “natural process” and that the environment should be “balanced” against energy and economy. However, courts upheld the necessity of enforcing the protections that congress had legislated. In 1978 Carter signed amendments to the Endangered Species Act that somewhat loosened its restrictions. (71-74)

On CLIMATE, given the energy crises of the 1970s, developing energy gained some priority over protecting the environment. Carter’s own proposals “balanced” the two; congress tipped the balance toward energy. It particularly rejected raising the prices of fossil fuels to encourage conservation and the development of alternatives. Nevertheless, after scientists publicized likely climate problems, in 1978 congress passed a National Climate Act that created a National Climate Program Office within the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (124). Unfortunately for climate, the EPA remained structured around the “media” carrying particular pollutants (air, water, soil) and decentralized to address local impacts. In the 2010s, that structure still impedes addressing a problem like climate change that involves many media and that is global in scope.

(On the Nixon-Carter period, see Layzer 2012 chapter three, “The Environmental Decade and the conservative backlash, 1970-1980.” On the particular roles of successive presidents, for Nixon see 33-41, Ford 41-45, and Carter 66-79. On particular subdomains under Carter, for pollution see 68-71, biodiversity 71-74, and climate/energy 74-76.)

Reagan-Bush 4.2

Coming to office in 1981, the Republican Reagan administration did not take the opportunity that existed for centrist reform of environmental regulation. Instead it launched an all-out assault on the Democratic liberal state, including its regulation of economic activity, particularly environmental protection. This radical conservatism was not specifically environmental, but provided strong polemical grounding for conservative anti-environmentalism. However, Reagan faced a congress that still contained many of the people who had established environmental regulation under Nixon , so Reagan could not simply overturn environmental legislation.

Instead, Reagan’s strategy was to weaken the institutions created to implement that legislation. He cut agency budgets and appointed political conservatives to run liberal agencies. He discouraged the enforcement of old environmental regulations and the drafting of new ones. The federal judiciary sometimes overruled those tactics. Nevertheless, in terms of policy, Reagan’s strategy was quite successful. For example, he delayed the USA’s dealing with acid rain for a decade. However, politically, Reagan’s strategy turned out to be too high profile and confrontational, provoking vigorous defense of environmentalism from both congress and public. During his second term, Reagan did not devote much attention to anti-environmentalism. In 1986 the Democrats, already in control of the House, regained control of the Senate, enabling them to reauthorize the Clean Water and Endangered Species acts, and even to pass a 1988 Global Climate Protection Act, which Reagan signed (Layzer 128-129).

Overall, the Reagan administration created the template for later radical conservatism, including radical anti-environmentalism. He laid the foundations for future conservative policies by rigorously reviewing his many judicial appointees for their conservatism, including their anti-environmentalism. His high profile all-out administrative attack on environmentalism polarized American environmental politics, making constructive policy compromise difficult, as it still remains today. (On the Reagan period see Layzer 83-133: first term 93-118, second term 118-128.)

In 1988 Reagan’s vice-president and heir George H. W. Bush, despite his own anti-environmental record under Reagan, embraced environmentalism in order to seek environmentalists’ votes. At the beginning of his term he did support some new environmental measures. These included an important 1990 addition to the 1970 Clean Air Act that combated acid rain by using cap-and-trade methods to limit emissions of sulphur dioxide. That quickly worked quite well, creating hopes for using cap-and-trade to mitigate other environmental problems, including climate change.

However, Bush’s new environmental measures revived business anti-environmentalism. Moreover, with the fall of communism, conservatives substituted anti-environmentalism for anti-communism as a critique of capitalism that they rejected. Renewed anti-environmentalism put ostensibly pro-environmental Bush in a political bind. Moreover, national economic difficulties strengthened his anti-regulatory economic advisers. Approaching the 1992 elections, Bush tacked back toward anti-environmentalism. Because Democrats controlled congress, he used low-profile tactics to weaken regulation, but that failed to appease anti-environmentalists. Meanwhile, the judiciary became increasingly anti-regulatory. These anti-environmental developments presaged renewed confrontation with environmentalism in the mid-1990s. (See Layzer 135-185, particularly 135-136.)

On POLLUTION, the first Reagan term obstructed restrictive laws, minimized the health risks from pollution, and emphasized the economic costs of regulation. Reagan particularly opposed measures to reduce acid rain, on grounds of scientific uncertainty. (93-98) Reagan’s first EPA administrator Gorsuch usefully experimented with using market mechanisms to control pollution. However, she reduced regulation, relaxed enforcement, and slowed the making of new rules (108-109). Her confrontationalism provoked such an outcry from congress and environmental advocates that Reagan replaced her with the also conservative but milder Ruckleshaus. Reagan’s second term EPA director Thomas enforced some environmental restrictions but avoided promulgating new ones, particularly on acid rain (120-123). Bush’s EPA director Reilly was a real environmentalist who strengthened enforcement and added protections against chlorofluorocarbons. Moreover he helped pass the pioneering cap-and-trade approach to controlling acid rain. (153-156). However, Bush’s Council on Competitiveness used low profile tactics to weaken implementation of the Clear Air Act (159-163).

On BIODIVERSITY, Reagan’s first Interior secretary Watt virtually halted protection of endangered species, though he failed in an attempt to weaken the definition of “harm” to species (106-108). Reagan replaced the confrontational Watt too with milder administrators, who however continued to give development priority over conservation. During Reagan’s second term, Interior continued to decline to implement conservation measures and decentralized administration to regional offices more vulnerable to local politics and economics (119-120). Bush’s Interior secretary tried to conciliate environmentalists but, as traditional at Interior, gave priority to development. He minimized protection for certain squirrels and owls, the latter by minimizing restrictions on logging (148-153).

On CLIMATE, Reagan marginalized Carter’s new climate organs and blocked funding for research on global warming – even while arguing against action because of scientific uncertainty! Nevertheless, in 1983 Reagan’s EPA released the first report by the American national government on the climate threat, predicting that it would begin to manifest itself in the 1990s. (123-125) During the unusually hot summer of 1988, climate scientist James Hansen forcefully told the Senate that climate change was imminent, making the issue prominent. At first it appeared that Bush might do something about it, but instead – on the advice of his political and economic advisers – he delayed action on the grounds of scientific uncertainty (156-159).

Clinton-Bush 4.3

By the time Clinton took office in 1993 (until 2001), environmental politics were still further polarized. On the one hand, as a mass movement, environmentalism had gained strength. On the other hand, conservative theorists dismissed regulation of pollution, conservative populists disparaged conservation of biodiversity, and conservative politicians dramatically gained strength. This polarization constrained Clinton’s ability to strengthen regulation. To disarm anti-environmental ideology, Clinton argued that environment and economy were compatible. To roll back previous Republican anti-environmental administration, he appointed environmentalists to run environmental agencies. However, by then, courts too had become more conservative and local officials had found implementing environmentalism costly. (On the Clinton period see Layzer 187-256, particularly her summary at 187-188 and the political overviews at 188-197 and 249-256.)

The George W. Bush administration (2001-2009) replayed the Reagan administration, but more successfully. Politically, the September 2001 terrorist attacks made politicians reluctant to challenge the president on anything, lest they appear unpatriotic. On policy, Bush appointed experienced anti-environmentalists to wreck environmental agencies. Unable to repeal environmental legislation, his administration deployed myriad low-profile anti-environmental tactics. It framed anti-environmental proposals in pro-environmental language, reworded rules, and changed their interpretation. It centralized control of rule-making and information, excluded climate scientists from policy-making, and even revised climate science! For much of Bush’s administration, congress was strongly Republican and increasingly conservative. The judiciary became steadily more conservative: strongly probusiness but not entirely anti-environmental. (On the Bush period see Layzer 257-332, particularly her summary at 257-258 and the political overviews at 260-272 and 329-332.)

On POLLUTION, under Clinton the EPA advanced a risk-averse agenda to control air pollution, an agenda whose advance conservatives could slow but not stop. EPA director Carol Browner – later Obama’s energy czar – defied rising conservative assault by stepping up EPA enforcement of existing rules (on equipment maintenance by power companies) and promulgating new standards for air quality (on soot and smog). At the same time, she introduced some flexibility into EPA regulation, “reinventing” it as more cooperative with those regulated. (197-223). After taking office in 2001, Bush repeatedly attempted to weaken the Clean Air Act with a allegedly pro-environment replacements (e.g., a Clear Skies Act). Congress rejected or courts overturned most of these attempted replacements. Bush’s early EPA did promulgate some restrictive regulations. However, under the influence of the extremely pro-energy vice president Cheney, the EPA later mostly resorted to low-profile tactics to weaken enforcement of existing regulations and discourage promulgation of new ones. These tactics substituted flexible market-based mechanisms for stronger administrative regulations. They also substituted voluntary compliance for strong enforcement. (272-295)

On BIODIVERSITY, Clinton Interior secretary Babbitt strongly favored protecting both species and their habitats. Nevertheless, under rising conservative assault, he tried to maintain those protections by placating anti-environmentalists. He offered to collaborate with landowners and developers and offered them positive incentives instead of negative sanctions. Bipartisan senate centrists proposed a bill to codify Babbitt’s efforts and to preempt more permissive legislation. These efforts by Babbitt and senators divided environmentalists into pragmatists willing to go along and idealists insisting on strict regulation. (223-238) Bush made the Endangered Species Act more permissive, substituting voluntary stewardship and financial incentives for mandatory compliance. Interior secretary Norton summarized this as “the four C’s – communication, consultation, and cooperation, in the service of conservation.” Bush also greatly slowed the listing of species as endangered and the designation of habitats as critical. He weakened relevant agencies by depriving them of resources and devolving responsibility to states and regions. In assessing the endangerment of species, Bush substituted risk-tolerance for precautionary judgment. He also encouraged litigation against protection of biodiversity, lawsuits that the administration then settled on terms friendly to developers. Environmentalists brought their own lawsuits, many successful, but not all. Meanwhile conservatives in congress directly challenged the Endangered Species Act itself, passing a substitute in the House that the Senate blocked. (295-315)

On CLIMATE, under Clinton, proponents of control became more concerned while opponents became more adamant. A control bill made it onto the agenda but conservatives (and coal state Democrats) defeated it. They prevented ratification of the international Kyoto Protocol by the Senate, constrained efforts to pursue the treaty’s goals through administration actions, and forced Clinton to propose only voluntary controls over the emission of greenhouse gases. (238-249)

Under Bush, conservatives had their greatest anti-environmental success in blocking action on climate. Bush entered office favoring climate control, but quickly reversed himself, giving priority to energy development instead. Soon thereafter he famously withdrew the USA from international negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol on climate control. Bush also obstructed congressional action on climate change by conservationist Republicans and Democrats. Instead Bush promoted voluntary climate control, which observers found ineffective.

Bush promoted comprehensive energy legislation: different versions passed the House and Senate in 2003, but a third version that reconciled the House and Senate bills failed in the Senate. The House bill had included provisions on climate change, which conservative Republicans in the Senate dropped, because they seemed to confirm that climate change was a real problem! In exchange for dropping those provisions, Republican senator McCain extracted permission to introduce a stand-alone climate change bill with six hours of floor debate, the Senate’s first on climate. In 2003 the Senate rejected the McCain-Lieberman Climate Stewardship Act 55 to 43, and again in June 2005 60-38. However, the Republican Senate then quickly passed a “sense of the Senate” resolution that – evidently under pressure from pro-control religious, business groups, and subnational governments – rejected the conservative definition of the climate problem. In a major victory for environmentalists, in 2007 the Supreme Court rejected Bush EPA claims that the Clean Air Act did not give it authority to regulate greenhouse gasses. Although complying domestically, the Bush administration resisted internationally, rejecting targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Finally in early 2008 Bush announced support for limiting greenhouse gas emissions, but continued to opposed most methods for doing so. (315-329)

______________________________________________________________________________

THE SCHEME OF THIS BLOG

DIMENSIONS OF POSTS

Importance of Post: ***** Big development. **** Small development. *** Continuing trend.

Scope of Post: USA only. USA-PRC. USA-other.

Type of Process: Elite power struggle. Elite policy politics. Mass participation.

Type of Treatment: Current commentary. Comprehensive background. Academic analysis.

DIMENSIONS OF POLITICS

Policy Sectors: Security. Economy. Identity

Spatial Levels: Supranational. National. Subnational

Temporal Periods: Shortrun. Midrun. Longrun

STANDARD TOPIC TAGS (BIAOQIAN)

SECURITY

Defense

Diplomacy

Intelligence

Presidency (national security team)

Homeland security

State coercion: Police & Prisons

Citizen violence: Collective riots & Individual harm

ECONOMY

Climate change

Trade & Investment

Fiscal policy

Macroeconomy

Energy & Environment

Business

Employment & Income

IDENTITY

Propaganda

Immigration

Ideology

Race & Ethnicity

Gender & Age

Moral regulation

Alternative lifestyles

SUPRANATIONAL

Global

United Nations

International regimes

Subglobal regions

Major foreign powers

Neighboring countries

Cross-border regions

NATIONAL

Legislative

Executive

Judicial

Parties

Interest groups

Media

Public opinion

SUBNATIONAL

Subational regions

States

Metropolitan regions

Cities

Counties

Communities & Associations

Citizen participation (elections, activism)

SHORTRUN (Current dynamics)

This week

Past few weeks

Next few weeks

Past few months

Next few months

Past few years

Next few years

MIDRUN (Foreseeable future)

Regime shift

Regime change

Trends

Cycles

Discontinuities

Variables

Parameters

LONGRUN (History, evolution)

American political development

Comparative political development

Longrun economic growth

Longrun social history

Longrun cultural change

Major civilizations

Human evolution

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号