140412

_____________________________________________________________

This is the second in a Series on how American Politics always involves interactions between several “levels”: national, supranational, and subnational. This time the interaction is between national parties and subnational publics, concerning which parties stand for what policies. This is important because, as it turns out, voting for parties on the basis of their “ownership” of particular policy domains is the main way American citizens influence national public policy.

_____________________________________________________________

140412

AMERICAN POLICY POLITICS: PARTY PRIORITIES, VOTER CHOICE

Patrick J. Egan 2013. Partisan priorities:

How issue ownership drives and distorts American politics.

New York NY: Cambridge University Press, 251 pages.

How exactly does American politics process policy ISSUES? Does the process differ across different kinds of issues? If so, what kinds of differences between issues are most important? In this process, what are the most important institutions – Constitutional branches such as congress, or extra-constitutional organizations such as parties? Are the policies government adopts the ones desired by a majority of Americans? Do institutions need improvement?

PARTY “OWNERSHIP” OF ISSUES

It is a common understanding of American politics that the Republican party now “owns” such issues as supporting the military, preventing crime, and lowering taxes, while the Democratic party “owns” such issues as health, education, and environment. The two parties compete to make “their” issues top the agenda during election campaigns, so that voters will vote for the party that “owns” those issues. (The end of this Post lists Americans’ policy concerns by party.)

These assumptions are so common – and so fundamental – that it is odd that it was only in the 1990s that political scientists began researching whether these assumptions are correct or not. As it turns out, they ARE largely correct, as thoroughly documented in Patrick Egan’s probing and rigorous 2013 book Partisan priorities. But Egan does a great deal more than simply confirm these general assumptions.

One thing Egan does is to identify the kinds of issues parties can “own” and the kinds they cannot. Parties can own only CONSENSUAL issues: most Americans agree that the goal is a GOOD, disagree only over how MUCH of that Good to purchase, or through exactly what policies. Given that public support, both parties support that Good too, to avoid losing votes. So on consensual issues parties move toward the political center.

Parties cannot own issues that are NONCONSENSUAL, such as reducing economic inequality, increasing (legal) immigration, and permitting abortion or gay marriage. To half of Americans (on the left), liberal policies on these matters are GOOD, to the other half (on the right), they are BAD. On nonconsensual issues, there are few voters in the middle, most toward the left or right, so the parties move toward those extremes.

Another thing Egan does is to distinguish between performance, policies, and priorities (aspects of each issue). Does a voter regard a party as “owning” an issue because that party, while in office in the past, has produced good results on that issue (PERFORMANCE)? Or because the voter likes the particular POLICIES that party promises to adopt on that issue? Or because the voter believes that party, when in office, will make that issue an over-riding PRIORITY?

As it turns out, the answer is neither performance nor policies. The public has little way to assess performance (in terms of actual results). Surprisingly, sometimes voters do NOT like the particular policies of the party they trust to manage a policy domain. What the public DOES understand and trust is a party’s commitment to priority for a policy domain, which to the public means that, if elected, the party will make a strong EFFORT in that domain.

This is odd and paradoxical. It is ODD because social scientists doubt that government effort in a policy domain actually does produce measurable results. It is PARADOXICAL because many Americans professes to believe that government is ineffectual and even counter-productive. Yet Americans continue to demand that government pass legislation and spend money on issues they care about!

EFFECTS OF PARTY OWNERSHIP

On the one hand, this setup “DRIVES” American politics, providing voters a significant “SAY” about which policy domains should be government priorities. An American who wants government effort at a stronger military and less crime can vote Republican. An American who wants effort at a cleaner environment and less poverty can vote Democratic. Either party will in fact deliver on its promise to adopt policies and spend money in “its” policy domains.

On the other hand, this voter “say” comes with a DISTORTION. On the issues they own, both major parties are committed to policies that are more extreme than those favored by the majority of Americans, who are mostly “centrist” on these consensual issues. So, having a choice only between the two main parties, Americans ALWAYS get policies that are more conservative or liberal than the majority prefers. Such distortion is a design flaw in American democracy.

With only two main parties, policies come in “packages.” An American who votes Republican because of one issue (say lower taxes) gets Republican priority on other issues as well (strong military, free trade, policing crime). Similarly an American who votes Democratic because of one issue (say environment), gets other Democratic priorities as well (X Y). In both cases, whether the voter likes that or not. This may be a limitation of any majoritarian democracy.

However, the American distortion is more severe. Once in office, party leaders work to fulfill their promise to make Effort on the policies their party owns. Paradoxically, the result is to make the “governing party” less RESPONSIVE to public opinion on the issues it owns than on other issues. The party’s longstanding priorities over-ride current majority public opinion. Members of congress disregard the majority views even of their own constituents.

Egan notes that one of the Goods that Americans want is lower TAXES, at the same time that they want more SPENDING on government programs. (This remains true even when the public is in a “small government” mood, as around the time of the 2010 election.) American politics seldom discusses this obvious contradiction. Are Americans too dumb to understand – or too selfish to admit – that contradiction?

No. The contradiction is seldom discussed because both pollsters and politicians present issues to the public one at a time, preventing the public from considering tradeoffs between policies and limits of funds. So American politics seldom gives Americans an OPPORTUNITY to address policy tradeoffs or total cost. Given an opportunity, Americans understand these contradictions and are concerned about them. Another design flaw in American democracy.

So, democracy requires institutions, institutions must be designed, and the DESIGN always involves TRADEOFFS. If you want to use mass political parties as the bridge between society and state, you must expect there to be some cost: the parties will be self-serving in some way, to some extent. Further “tweaks” of the design – such as reducing the influence of activists – may reduce the cost, but probably can’t eliminate it entirely.

ELABORATION OF FINDINGS

Party ownership of issues requires convergence of all three major “ASPECTS” of “party.” First is the PARTY GOVERNMENT: the party leaders who run the government after the party wins an election. Second, is the PARTY ORGANIZATION: the “rank an file” who remain active in the party organization whether it is in or out of power. Third are the PARTY VOTERS, at least those who identify with a party as partisan Republicans or Democrats.

Egan’s data show that, on issues that parties own, all three of these aspects of party DO converge with each other, and also with public perceptions of which party owns which issues. Such issue ownership remains quite stable over time, because it takes a long time for all three of these aspects of party to change their minds about an issue, and for the general public (beyond the party’s own partisans) to understand and accept that change.

Party leaders (mostly the president) DO sometimes make Effort in policy domains that the Other party owns, attempting to steal that issue, or at least to preempt attacks from the Other party concerning that issue. Such TRESPASSING can be surprisingly effective, but only in the short run. Permanently owning an issue requires realignment of all three aspects of party, and of public perceptions of party.

Examples of trespassing include the following. Clinton rather successfully promoted free trade, reformed “welfare” and fought crime. Bush promoted education (somewhat successfully) and advocated reforming Social Security (unsuccessfully). Obama has been careful to support a strong military (the “surge” in Afghanistan) and to combat “illegal” immigration (deporting “illegals”). In the short run, such trespassing DID weaken the Other party’s ownership of those issues.

As noted above, party ownership of most issues is unrelated to party Performance on that issue, because usually Performance is hard to assess performance. Nevertheless, Performance is easier to assess on some issues, such as the Economy and Foreign Policy, which may “move” between parties. Since the 1970s, the Economy has moved between Democrats and Republicans several times. In the 2000s, Foreign Policy moved from Republicans to Democrats.

Distortion on issues seems obviously related to another design flaw in American democracy, distortion on candidates. Activists vote more in party primaries than ordinary party members and so have more say over NOMINEES, who therefore are more extreme than ordinary party members, not to mention the American public as a whole. But ordinary party members have little choice but to vote for those nominees in the general election.

The Packaging and Distortion of issues helps explain a recurrent pattern in American politics: after voters elect one party, their ideological “mood” swings toward the other party, as the elected party adopts policies many voters don’t like. One could regard this “inaccuracy” of representation and “instability” of government as a design flaw. Or one could regard it is an advantage: American politics encourages alternation of parties in power.

CONCERNS ABOUT PROBLEMS

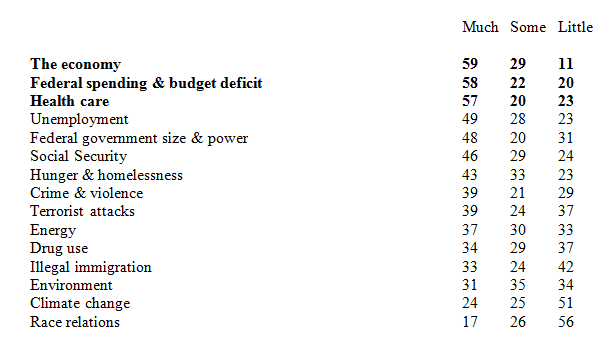

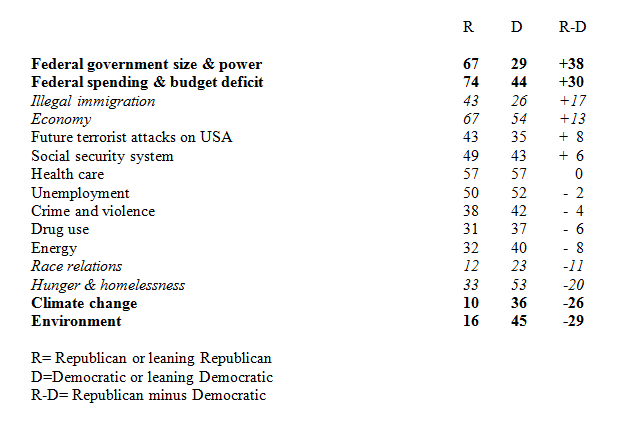

A main source of “partisan priorities” is the fact that supporters of the two major parties are concerned about different policy problems. These are the problems on which those partisans trust their party to make an Effort and that most Americans regard as being owned by that party. The following is the kind of 2000s data on which Egan relies for documenting recent differences in priorities between partisans. The list first shows Americans as a whole, then by party.

____________________________________________________________

AMERICANS’ LEVEL OF WORRY ABOUT NATIONAL PROBLEMS

2014 RANK ORDER, GALLUP 6-9 March 2014

% that worry “a great deal” (“much”), somewhat, and little or none (“little”)

AMERICANS’ CONCERNS ABOUT US ISSUES – BY PARTY

GALLUP 6-9 March 2014

% that worry a great deal (“much”), ranked by difference between parties

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号