140322

_____________________________________________________________

SERIES: This is the last in a Series about recent reinterpretations of major episodes in American Political Development. This Post notes continuities before and after the Civil War and looks forward to the whole 1877-1962 period. A later Series will treat episodes after 1877 individually.

_____________________________________________________________

Political scientists are rethinking the overall shape of American Political Development, particularly successive configurations of issues and parties. This Post reports an important reinterpretation of the whole period from 1877 until 1962! (Alan Ware 2006. The Democratic party heads north, 1877-1962. New York NY: Cambridge University Press, 281 pages.)

Ware displays much mastery of American subnational politics. He argues that states and their voters have moved only slowly between parties, if at all. What really moved were the parties themselves, probing the country for votes. Ware presents much detail on successive episodes. This Post reports only his general themes. A later Series will treat the episodes.

DYNAMICS

Oxford political scientist Ware does NOT regard 1877-1962 as a separate “era” in American Political Development. Indeed, his main point is the remarkable CONTINUITY of American politics, not only within the 1877-1962 period, but also before and after. American politics “develops,” but only gradually.

“Politics” here means PARTY politics, and in particular the evolution of the DEMOCRATIC party.

Party politics are central because, since the advent of Mass Democracy in the 1820s, parties have been the main way of organizing American politics. “How parties related to mass electorates was much the same in the 1880s as it had been in the 1840s.” (14)

The Democratic party requires particular attention because, after the Civil War and Reconstruction, Democrats faced the problem of supplementing their main base in the South with at least SOME votes from the North and/or West. (Republicans had to supplement their main base in the North, but could do so more easily than could Democrats.)

HISTORIANS’ main account has been that Democrats were the majority party before the Civil War and Republicans after the Civil War (until 1932!), as reflected in how often each party captured the presidency (very different before and after the Civil War).

In Ware’s account, after the Civil War, a few formerly Democratic states (Maine, Michigan, Pennsylvania) DID shift sharply Republican. But, contrary to widespread impression, the Civil War did NOT create an overwhelmingly Republican North.

POLITICAL SCIENTISTS’ main historical account has been that the USA has had a succession of significantly different “party systems,” each with its own distinctive set of issues, parties, and even voters.

Some political scientists are now strongly criticizing that classic “realignment” story. (David R. Mayhew 2002. Electoral realignments: A critique of an American genre. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 174 pages.)

As noted above, an ALTERNATIVE is to stress continuity. Voters in different regions continued to prefer either more government or less government and even to prefer the same parties. What changed most were parties’ strategic decisions about whom to appeal to, where, on what basis.

Thus the core dynamic in Ware’s account is COALITION-BUILDING: putting together some nationally winning combination from the particular subnational “building blocks” available to either party. The blocks themselves changed only slowly over time.

Over the long run, the result has been a remarkable flip-flop in which the Democrats, originally appealing mostly to the small-government South, by the 1960s end up appealing mostly to the big- government North. Ware’s 2012 book explains how they managed to do that.

Several factors complicated the Democrats’ coalition-building. First, the 1787 Constitution prescribed an electoral system that tends to produce two major parties. In a two-party system, winning coalitions have to be quite broad and therefore quite heterogenous.

Second, as the USA admitted new states, the states involved kept changing, in number, size, and nature of. In the 1800s, Democrats could win a national majority by coopting only a half-dozen largish states outside the south. By the 1900s, they needed many more and mostly smaller states.

Third, although the socio-spatial base of the Democratic party changed only slowly, it DID change gradually: with the slow succession of generations, the arrival of many more immigrants, and the admission of new states.

LEVELS

The American political chessboard is MULTI-LEVEL: different opportunities, constraints, and outcomes at different levels. Previous accounts have focused on which party won which national offices, particularly the presidency. Ware looks also at state governors and even state legislatures.

To win the presidency, Democrats needed votes in the Electoral College, chosen by STATE. Outside the South, Democrats had to win about 21% of the electoral votes in the old North and new West. (Presumably about the same for capture the Senate, also elected by state.) (15)

To win a majority in the House of Representatives – elected from smaller substate districts – Democrats had to win about 30% of northern districts. To do that they had to appeal both to their large southern base and to particular kinds of northerners. (15)

One of Ware’s main points is that the Democrats did NOT completely lack support outside the South. Indeed, even AFTER the Civil War and Reconstruction, they remained competitive in many northern states and became competitive in others. (Please see Table below.)

Accordingly one of Ware’s main themes is that, as before the Civil War, so also after the Civil War, the Democrats still had the “building blocks” from which to assemble a nationally winning coalition. Their real problem was to overcome potential conflicts between those blocs.

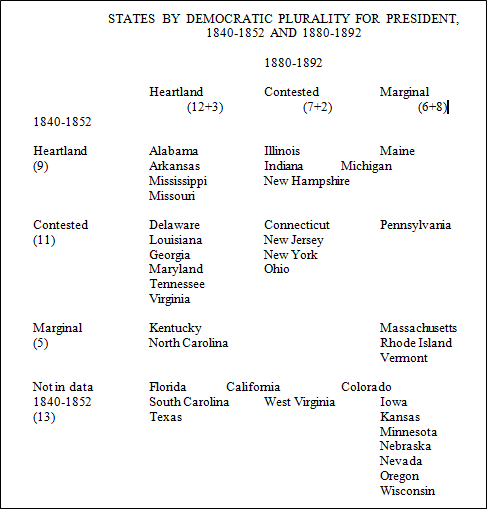

The following Table shows the great continuity in the Democrats’ subnational bases before and after the Civil War (adapted from Table 1.1 in Ware 2012, page 12). “Heartland” states are where Democrats got a strong vote for president (a median plurality of more than 5% of the total vote).

Note that, before and after the Civil War, the Democrats’ old heartland states remained heartland (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri). Moreover, “contested” southern and border states in which before the Civil War the Democrats had been only competitive, after the Civil War became heartland (Delaware, Louisiana, Georgia, Maryland, Tennessee, Virginia). Furthermore, states on which there are no voting data for 1840-1852 turn up in the Democrats’ heartland in 1880-1892 (Florida, South Carolina, Texas). So, after the Civil War, the Democrats commanded a formidable heartland, mostly in the South (though they did not completely monopolize the South until the 1890s when the South again repressed black voting).

Note also that, after the Civil War, the Democrats remained competitive in several northern states (Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Ohio). Meanwhile, they became competitive in several more northern states (Illinois, Indiana, New Hampshire). The Democrats were also competitive in two states that were not in the 1840-1852 data (California and West Virginia). So, after the Civil War, the Democrats had plenty of states in which they were competitive and that therefore they could try to add to their southern base in order to form a nationally winning coalition

Evidently in the 1850s the issue of slavery was ADDED to previously existing issues. Once the slavery issue was resolved, the old issues re-emerged and, with them, many of the earlier state alignments. (13) So let us turn to issues.

SECTORS

Coalition-building required identifying combinations of specific IDENTITIES and INTERESTS that were compatible with each other, or at least that could be made to appear compatible under the right general IDEOLOGY. Party ideologies were both highly strategic and deliberately vague.

1800s parties were still mostly ad hoc national alliances of local Identities. In the 1990s, Interests also became important building blocs. But parties could not really use national POLICIES to recruit new support until the 1930s, when national revenue greatly increased.

Core Democratic support came from southern agricultural interests still favoring small government. Later the same anti-government principle appealed to Catholic immigrants in North (East) cities, who did not want moralistic Protestant Republicans to use government to “improve” them.

Core Republican support came from northern industrial and commercial interests, including “eastern” finance. Republicans also retained the support of “Yankees” (northeast, New England), including those who settled much of the upper Mid-West as prosperous farmers and businessmen.

Republican commitments to business and finance gave Democrats an opportunity to appeal to West “primary” producers: small farmers and mineral miners (populists). However, these populists tended to be quite radical, which alienated other potential Democratic allies.

Indeed, Democratic national coalition-building was crippled in 1896, 1900, and 1904 when populist William Jennings Bryan won the Democratic nomination for president. In 1912 and 1916, moderate Democrat Woodrow Wilson won both nomination and presidency (against divided Republicans).

Because of “culture war” over drinking between “wet” East and “dry” West, Wilson could not coop the West permanently. In the 1930s, after Prohibition, Franklin Roosevelt finally succeeded in doing so. He also BEGAN to coopt labor in northern cities. But doing so fully took until 1962.

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号