140222

_______________________________________________________________

Ending a Series, this last Post on Political Economy notes that it is the main general DIMENSION of issues in American politics. The first Post (140201) outlined the alternation, in the course of American political history, of impulses toward more and less governance of the economy. The second Post (140208) highlighted the political components of economic cycles. The third Post (140215) focused on specifically Financial institutions, the core of current economies, but crucial in the past as well.

_______________________________________________________________

Recent work on American Political Economy provides American political science with an extraordinary resource – precise measurements of the POSITION on major issues, not only of currently active politicians, but also of all Members of Congress (MCs) from 1791 to the present. Thousands of “roll call” votes in the Senate and House have revealed and recorded MCs stands on the main issues of their day. Analyzing this data produces a series of insights, not only into the current structure of American politics (such as polarization) but also into fundamental and enduring structures (including historical variability in polarization). That result is relevant to a Series on Political Economy because a principal finding of this research is that a basic issue of political economy – the extent to which “government” should or should not intervene in the “economy” – has usually been the main general DIMENSION of issues in American politics.

This recent work contains HISTORICAL analysis of cleavages that continue into the present, RECENT analysis of the extent and concomitants of recent polarization, and CURRENT analysis of some major votes in congress as they continue to occur. So it is worth familiarizing oneself with this work and worth learning how to read the charts that display results. This Post reprises some of its findings (some of it noted in previous Posts, particularly 13406, second part).

(The main portal to this work is Keith Poole’s website . The first main published result was Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal 1997. Congress: A political-economic history of roll call voting. New York NY: Oxford University Press, 297 pages. The more recent revised version is Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal 2007. Ideology & Congress (2nd rev. ed). New Brunswick NJ: Transaction Publishers, 344 pages. See also Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal 2006. Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 240 pages.)

Poole and his colleagues call their dimensions “ideological.” Here ideology is formulations by politicians that serve various political purposes. First, helping the national leaders of the two main parties appeal both to the general public and to specific “publics.” Second, helping congressional leaders assemble issues into legislative proposals, particularly proposals that will achieve the results that congressional leaders themselves want. Third, helping leaders of parties in congress organize and discipline their party members for debating and voting on those proposals. Together, these uses produce formulations that greatly simplify the myriad issues that arise in society. The result is to keep the number of issue Dimensions low, which in turn helps keep the American polity stable.

In American political science, a famous definition of ideology is “what goes with what.” To some extent, “what goes with what” MAY actually have some philosophical consistency. Many leaders and politicians want to believe that. Many claim that they themselves are ideologically consistent – not just along the main political-economic dimension, but even across the political-economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Nevertheless, “what goes with what” is basically political: what, under given political circumstances, a party or politician happens to find expedient – what issues to raise and what stands to take on those issues.

(Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal invented a new method for analyzing data such as roll call votes. The method is called NOMINATE: Nominal Three-Step Estimation. It has been improved in the course of several versions: D, W, DW. The Wikipedia article on “NOMINATE (scaling method)” is helpful, with good illustrations. An in-depth introduction is Everson-Valelly-Wiseman at .)

FINDINGS

To repeat, for American Political Development, the main finding is that the main dimension of American politics has usually been a political-economic one: the extent to which government should or should not regulate the economy or intervene in it. Sometimes during American Political Development there has even been almost the only dimension. That was true in the late 1800s, and again now in the early 2000s. One might think that, in general, a preoccupation with political economy is what one should expect from democratic politics in a capitalist society. The recent work of Poole and his colleagues confirms that.

However, their work also highlights the distinctiveness of the specific American version of capitalist political economy. One distinctiveness derives from the USA’s federalism: Historically, much of the disagreement has been over the extent to which the NATIONAL government should intervene in the economy, as opposed to state governments, which originally managed most economic issues. Recently, political-economic disagreement has become more abstract and more absolute: the extent to which ANY level of government should interfere in ANY way with ANY outcome of markets.

Oddly, although the political-economy dimension itself has persisted through most of America’s political history, around 1900 the two major parties switched sides on that dimension! The Democrats, representing small interests, went from wanting the national government to leave localities alone to wanting it to regulate Big Business. Accordingly the Republicans, representing Big Business, went from wanting the national government to help Big Business to wanting the national government to refrain from regulating Big Business. (Probably facilitating this remarkable flip-flop was the migration of the two main parties between regional bases, particularly the extension of the Democratic party from South to North. See Alan Ware 2006. The Democratic party heads north, 1877-1962. New York NY: Cambridge University Press, 281 pages.)

Another distinctiveness of American politics has been exactly how political economy has interacted with other issues. The other main dimension has usually been what one might call socio-cultural: classically, North versus South on slavery and civil rights; increasingly, urban versus rural on so-called “social” issues of cultural values or “life-styles”. The importance of this second issue dimension has periodically increased and decreased, relative to political-economy. In the run-up to the Civil War, a socio-cultural issue (the morality of slavery) became the most important issue.

A finding at the level of individual MCs is that ideological change occurs, not because individual politicians change their minds, but through the replacement of incumbent politicians by new politicians, often from a different party. Once a politician takes up a position along an issue dimension, the politician seldom changes that position. For example, in response to recent economic crisis, American politicians have doubled-down on their original ideological positions, not concluded that they need to revise them. Arguably, the main reason for such ideological consistency is the need of politicians, for electoral purposes, to appear “principled”: to have coherent convictions and to stick to them over time, reliably representing constituents with those same convictions.

ANALYSIS

An important property of politics is polarization: the degree of separation between ideologies and parties. (See McCarty-Poole-Rosenthal 2006 Polarized America. Most recently, Hare & Poole 2013 at )

Historically, the more one-dimensional the politics, the greater the polarization. In the case of the Civil War, socio-cultural polarization was so great that half the country seceded! Evidently political-economic issues, being quantitative, are more amenable to compromise. Evidently socio-cultural issues, being qualitative, are less so. An aspect of recent polarization of American politics is that the political-economic dimension has absorbed most socio-cultural issues, making it more difficult to compromise even on economic issues.

The more two-dimensional the politics, the less the polarization. The main example is from the 1930s to the 1960s, when the strong cleavage between Northern and Southern Democrats created a virtual three party-system (with Republicans). Each of the three parties allied with different partners on different issues, It was this period that made Americans expect that politics should often be “bipartisan.” The early 2000s have sorely disappointed that expectation.

A further tantalizing general pattern is the coincidence, from the late 1800s to the 2010s, of the degree of political polarization and two other main variables: the extent of economic inequality and the extent of immigration. Polarization, inequality, and immigration were all high in the late 1800s and again in the late 1900s, but all low in between. Was this JUST a coincidence, or were there causal relationships between the three? If so, in what direction? Did economic inequality cause political polarization, or the reverse? Did immigrants matter by contributing to economic inequality or by their (low) political participation? Political scientists continue to debate. Regardless, the findings are striking and the historical patterns are useful to remember.

All of this bears on still more fundamental properties of American Political Development and on fundamental theories of politics. One property is dimensionality: to Poole and his colleagues, it is important that American politics has always been “low dimensional” (usually only two dimensions at most). According to some theories (“impossibility” theorems), politics becomes unstable when politicians faces too many issue dimensions. The possibilities for forming coalitions become too numerous, inhibiting the formation of ANY constructive coalitions. That is another way of interpreting the 1850s leading to the Civil War.

(So far as I know, current analysis has not yet specified exactly what the additional dimensions were in the 1850s. One possibility for analysis is to make use of the obvious fact that the North-South split was not only socio-cultural but also military-political: a basic political issue of sovereignty and stateness. Then one might ask, was the problem leading to breakdown that there were too many dimensions or that one of them was military-political? This Blog hopes to look further into the 1850s. After all, that was the one time in American political history when the American polity completely broke down. So that episode should help one understand that polity’s basic characteristics and changes in those characteristics over time.)

PRESENTATION

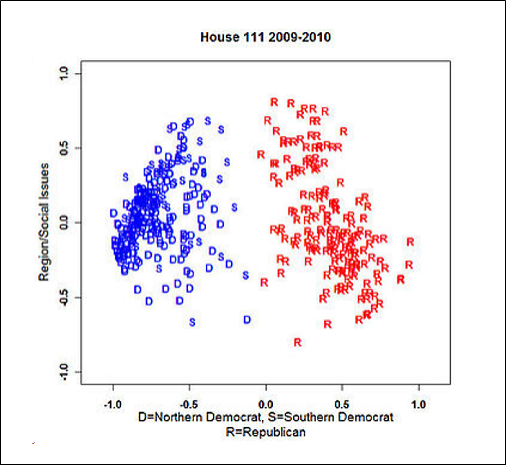

The NOMINATE work is so useful, it is worth learning to read the charts that display its results. (For an example, please see the end of this Post.) Actually, the charts are quite simple and intuitive: they show the positions of individual politicians (sometimes whole state delegations), in a two-dimensional space: left to right (political-economic) and bottom to top (socio-cultural). The charts show Democrats and Republicans (Ds and Rs) in different colors. Often the charts distinguish northern Democrats (Ds) from southern Democrats (Ss). When polarization is low, the parties overlap in the middle. When polarization is high, MCs cluster to left and right or bottom and top. When two dimensions are influential, often MCs cluster toward corners.

Often a line shows the likely “cut” between those who will vote for or against a proposition, given the known ideological propensities of the MCs involved. When the line is vertical (or nearly so), it divides left from right: political-economy is most important. When the line is horizontal (or nearly so), it divides top from bottom: the socio-cultural dimension is most important. When the line is diagonal, both dimensions are somewhat important.

Charts can display the relative positions of all MCs on a particular vote on a particular issue. The NOMINATE methodology can also calculate and display the average position of each MC during any two-year session of congress (“ideal point”). From this, NOMINATE can calculate the exact ideological position of all MCs in USA history and also the relative ideological positions of selected politicians. (For example, the second Bush was MUCH more conservative than Ronald Reagan.) Poole has even assembled the displays for successive congresses into a continuous video. It looks like a cartoon, but it displays the entire history of American politics, based on precise data, in a minute or two!

Imagine if Chinese could have an exact measurement of the policy positions of late Qing imperial ministers, Republican era Nationalist officials, and PRC communist leaders – all in the same terms! Imagine if one could say definitively for modern China what the main issues have been and how they have evolved! Of course, that will never be possible because, unlike in America, in China political institutions and political issues were not continuous from the 1790s through the 2010s. People like to say that China is an old nation and America is a new nation. But, institutionally, the USA has a much longer history than the PRC.

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号