130126

AMERICAN GUN POLITICS: A GUIDE (PART TWO)

______________________________________________________________________________

DIMENSIONS OF POLITICS DIMENSIONS OF POSTS

Sector: Security Importance: ****

Level: Subnational Scope: USA only

Period: Shortrun Process: Policy politics

MAIN TOPIC: Violence Treatment: Analysis.

____________________________________________________________________________

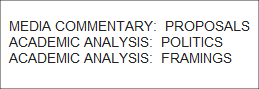

MEDIA COMMENTARY: PROPOSALS 1

Obama’s proposals 1.1

Technical feasibility 1.2

Political feasibility 1.3

ACADEMIC ANALYSIS: POLITICS 2

Limited regulation 2.1

Missing movements 2.2

Policies make politics 2.3

ACADEMIC ANALYSIS: FRAMINGS 3

Security 3.1

Identity 3.2

Economy 3.3

READINGS

_____________________________________________________________________________

This Post is the second half of a Guide to American gun politics. Last week (130119) the first half covered basic Background and initial reactions to the Newtown shootings in December. This week the second half notes January proposals for gun reform and introduces some academic analysis of American gun politics in general.

Thus the first third of this Post summarizes and discusses the PROPOSALS for gun reform assembled by vice-president Biden and endorsed by president Obama. The second third sketches some academic analysis of the patterns of POLITICS that gun issues produce. The last third notes academic analysis of the alternative “FRAMINGS” that gun issues can receive.

References occur throughout this Post as relevant. Last week’s Post provided a basic list of recommended readings. This Post frequently cites an early skeptical analysis of the efficacy of “gun control”: William J. Vizzard 2000 Shots in the dark: The policy, politics, and symbolism of gun control. Landham MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 257 pages.

COMMENTARY: POLICIES 1

The first third of this section details Obama’s policy proposals. The middle third discusses the technical feasibility of some key proposals for improving the information available to assist the regulation of guns. The last third addresses the political feasibility of Obama’s proposals and their place in Obama’s overall political strategy for his second term.

Overall, there is a political and policy paradox: public revulsion at suburban gun rampages creates a demand to “do something” about a problem that, realistically, gun policy can little affect. This CAN provide an opportunity for progress in related areas, such as staffing schools, funding mental health, and limiting violence in entertainment. However, the difficult question becomes, is demand to “do something” about suburban gun rampages sufficient to spill over into doing something about the real problem – chronic inner-city gun violence. (See Pastor Michael McBride 130114 “Gun violence task force must address inner cities” on The Congress Blog at . Also Michael Cooper, Michael Luo and Michael D. Shear 130115 “Obama gun proposal to look beyond mass shootings” at .)

Obama’s proposals 1.1

Obama’s proposals fall into Ten Main Strategies and involve some 23 Executive Actions.

MAIN STRATEGIES. According to one good summary, Obama is Pursuing Ten Main Strategies. Below I group them under three main categories. (See Brad Plumer 130116 “Obama’s plan to reduce gun violence.” Also Matt Vasilogambros 130116 “What are Obama's gun control proposals? An easy guide” at .)

GUN SALES

1 Require a CHECK of ALL gun buyers for criminal background.

2 Ensure that INFORMATION on dangerous individuals is available for background checks.

3 Reinstate and strengthen 1994-2004 ban on ASSAULT WEAPONS.

4 Restore the 10-round limit on magazines of AMMUNITION.

LAW ENFORCEMENT

5 Protect police by finishing the job of getting rid of armor-piercing BULLETS.

6 Give law enforcement additional TOOLS to prevent and prosecute gun crime.

7 End the freeze on gun violence RESEARCH.

ENVIRONMENT

8 Make SCHOOLS safer: more police and counselors, better emergency response plans.

9 Ensure that young people get the MENTAL HEALTH treatment they need.

10 Ensure that health insurance plans cover MENTAL HEALTH benefits.

Some of these proposals require congressional action, some not. As discussed below, Obama is well aware that some of the ones that require congressional action may not pass congress – particularly not the Republican-controlled House, but even the Democratic-controlled Senate.

EXECUTIVE ACTIONS. Accordingly, using his own executive authority, Obama will immediately take 23 Executive Actions on guns and gun violence. This certainly constitutes vigorous executive action. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Obama has attempted to keep these “executive actions” uncontroversial. That is, either they fall well within the scope of what congress has authorized the president to do, or they are simply administrative instructions to subordinates within the executive branch. None of them are the more controversial “executive orders” that have the force of law and sometimes attempt to “stretch” executive powers. Republican howls of “presidential over-reach”are overdrawn. This is particularly so of the eccentric Texas congressman who wants to impeach Obama for abuse of power. (See Josh Gerstein 130116 “Gun advocates shrug at Obama’s executive actions” at . Also Ginger Gibson 130114 “Rep. Stockman threatens Obama impeachment over guns” on On Congress at .)

The groupings below show the heavy emphasis of Obama’s executive actions on Background Checks (six items), Law Enforcement (five items), followed by Mental Health (four items). The categories are again mine.

BACKGROUND CHECKS: INFORMATION AVAILABILITY

1 Issue a Presidential Memorandum to require federal agencies to make relevant data available to the federal background check system.

2 Address unnecessary legal barriers, particularly relating to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, that may prevent states from making information available to the background check system.

3 Improve incentives for states to share information with the background check system.

BACKGROUND CHECKS: FEDERAL GUIDANCE

4 Direct the Attorney General to review categories of individuals prohibited from having a gun to make sure dangerous people are not slipping through the cracks.

5 Propose rulemaking to give law enforcement the ability to run a full background check on an individual before returning a seized gun.

6 Publish a letter from ATF to federally licensed gun dealers providing guidance on how to run background checks for private sellers.

GUN SAFETY

7 Launch a national safe and responsible gun ownership campaign.

8 Review safety standards for gun locks and gun safes (Consumer Product Safety Commission).

LAW ENFORCEMENT

9 Issue a Presidential Memorandum to require federal law enforcement to trace guns recovered in criminal investigations.

10 Release a DOJ report analyzing information on lost and stolen guns and make it widely available to law enforcement.

11 Nominate an ATF director. [The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, the main federal agency responsible, has lacked a congressionally-confirmed director for six years!]

12 Provide law enforcement, first responders, and school officials with proper training for active shooter situations.

13 Maximize enforcement efforts to prevent gun violence and prosecute gun crime. [This focuses enforcement on what policy can most affect.]

RESEARCH

14 Issue a Presidential Memorandum directing the Centers for Disease Control to research the causes and prevention of gun violence.

15 Direct the Attorney General to issue a report on the availability and most effective use of new gun safety technologies and challenge the private sector to develop innovative technologies.

MEDICAL SYSTEM

16 Clarify that the Affordable Care Act does not prohibit doctors asking their patients about guns in their homes.

17 Release a letter to health care providers clarifying that no federal law prohibits them from reporting threats of violence to law enforcement authorities.

SCHOOL SAFETY

18 Provide incentives for schools to hire school resource officers. [A euphemism for armed policemen to guard schools.]

19 Develop model emergency response plans for schools, houses of worship and institutions of higher education.

MENTAL HEALTH

20 Release a letter to state health officials clarifying the scope of mental health services that Medicaid plans must cover.

21 Finalize regulations clarifying essential health benefits and parity requirements within ACA exchanges.

22 Commit to finalizing mental health parity regulations.

23 Launch a national dialogue led by Secretaries Sebelius and Duncan on mental health.

Technical feasibility 1.2

Two items among Obama’s gun reforms are more difficult and important than their names convey. One of these is extending checks on the backgrounds of would-be gun purchasers to a larger part of gun sales. The other is resuming federal research – and funding for private research – on the causes and consequences of violence involving guns. Both of these items are important for increasing the INFORMATION available to regulators. Recently, by conservative congressional design, executive regulation has been “flying blind.” These items involve two questions of “technical feasibility”: Are the items themselves technically feasible? What effect would their implementation have on the technical feasibility of regulating gun violence? (On the overall technical feasibility of Obama’s proposals, see Brad Plumer 130115 “Obama is rolling out his gun proposals soon. Here’s what you need to know” and Brad Plumer 130116 “Gun experts grade Obama’s proposals,” both on Wonkblog at .)

EXTENDING CHECKS: Thus one item in Obama’s proposals that requires explanation is the first of the ten main strategies: “Require a CHECK of ALL gun buyers for criminal background.” The current system requires such background checks only for the most formal of gun sales, which are only a part of the total. Extending the checks to a larger part of sales will help limit gun violence, particularly by helping law enforcement trace transactions across state boundaries, in order to identify criminals who are most likely to commit gun violence. However, extending the checks very far is technically almost impossible. (See Brad Plumer 130116 “Obama wants universal background checks for gun buyers. Is that feasible?” on Wonkblog at .)

To understand why, we must briefly overview the current system for regulating gun transactions. It focuses on a formally regulated primary market but does not regulate a legal secondary market and an illegal tertiary market. The government licenses dealers to buy and sell in the primary market. However, licensed dealers also sell from the primary market into the secondary market, and guns leak freely from the secondary market into the tertiary market. Across all three types of markets, legal and illegal sales of guns are so intertwined as to confound enforcement. Besides, most people who might want to use a gun can simply borrow one from someone.

RESUMING RESEARCH. Another item in Obama’s proposals that requires explanation concerns RESEARCH (the seventh of the ten main strategies and the fourteenth of the twenty-three executive actions). In 2006 a Republican congress passed a law forbidding federal support for research intended to promote gun control. Since ANY research on gun violence could be construed as promoting gun control, federal funding of such research virtually ceased. Since most such research has depended on federal funding, research itself virtually ceased. As a result, by the design of conservative congresses acceding to the wishes of the Gun Lobby, evidence-based policy making on gun matters has become impossible – ABSOLUTELY DISGRACEFUL for the supposedly most scientifically advanced nation on earth! Here are some of the things that we don’t know but MIGHT now find out. (Obstacles to funding remain.)

How many guns actually exist in the United States?

How do guns get into the hands of people who commit crimes?

What percentage of gun owners even commit gun crimes?

Is there a relationship between gun ownership levels and crime?

Are criminals deterred by guns?

Do limits on high-capacity magazines reduce the number of deaths?

Does firearm licensing and registration make people safer?

How do gun thefts affect crime rates?

Does gun ownership affect whether people commit suicide?

What’s the best way to restrict firearm access to those with severe mental illnesses?

Why do gun accidents occur? Who’s involved?

(See Brad Plumer 130117 “Gun research is allowed again. So what will we find out?” on Wonkblog at , Plumer cites Emily Badger 130116 “Questions About gun violence that we may now be able to answer” at . Plumer also provides other valuable links on this topic.)

Overall, because national gun legislation occurs only infrequently, the national legislature neither maintains nor commissions relevant expertise on such things as how guns are actually used and how gun markets actually work . For example, the haphazard way in which regulations have defined “bad” guns has allowed manufacturers to make only nominal changes that have easily moved problematic weapons out of the “bad” category into the permissible. (Vizzard 2000)

Political feasibility 1.3

The simplest question about the political feasibility of Obama’s proposals for gun reform is: can the ones that require congressional legislation pass both chambers of congress? Some, such as extending background checks, probably can: Even the NRA supports them, since it diverts attention from guns to owners. Other proposals, such as banning large ammunition magazines, MIGHT pass the Democratic Senate but probably would NOT pass the Republican House. Still other proposals, such as banning “assault weapons,” might NOT pass even the Democratic Senate and certainly not the Republican House. (See Sean Sullivan 130116 “What President Obama proposed on guns. And what might actually pass Congress” at . On the Senate, see Manu Raju and Ginger Gibson 130116 “Senate forecast for guns: Cloudy” at . On the House, see Jonathan Martin and Jake Sherman 130116 “Why President Obama's gun plan may be doomed” at .)

A slightly more complex question concerns legislative strategy. Obama has the option of proposing one large bill that contains everything he wants. However, he will probably choose to submit separate bills, so that the more acceptable proposals can pass even if less acceptable proposals fail. In particular, even though he is proposing a ban on assault weapons, he may be prepared to sacrifice that so that other proposals can pass. Then opponents of gun control can defend a vote in favor of those proposals on the ground that they defeated the ban on assult weapons. Thus assault weapons could play somewhat the role that the “single-payer” option played in health reform – something that had to be sacrificed, but whose sacrifice facilitated passage of other reforms. (See Justin Sink 130117 “Carney: White House to pursue separate gun control bills in Congress” at . And, particularly, Ezra Klein 130117 “How (most of) Obama’s gun control plan can pass Congress” on Wonkblog at .)

A larger question of strategy concerns Obama’s new approach to negotiating policies and winning politics. During his first term, Obama tried to conciliate Republicans in order to gain their support, but they gave him no support whatsoever. Moreover, Obama chose not to waste political resources by fighting to pass legislation in the Senate that he knew could not pass in the House. During his second term, evidently Obama intends to propose what he actually wants and simply overwhelm Republican opposition. Moreover, evidently he may be prepared to insist that the Democratic Senate pass legislation that everyone knows can’t pass the Republican House. The resulting contrast between chambers could help dramatize to the public that it is Republicans who are being intransigent and therefore help mobilize public opinion in support of Democratic proposals. (Chris Cillizza 130116 “President Obama’s new negotiating tactic: Stop negotiating with yourself” on The Fix at . Glenn Thrush 130116 “Why President Obama might choose to lose on guns” at .)

Nevertheless, that strategy carries risks for Obama and Democrats. A classic strategy in politics is to choose issues that unify your side and divide your opponents’ side. As noted in a previous post (130112), some of the issues and appointments that Obama is putting on the agenda for his second term – immigration, fiscal crisis, disaster relief, a moderate Republican for secretary of state – tend to divide Republicans. However, the gun issue is one that divides Democrats. The reason is that, in 2006 and 2008, Democrats recaptured congress from Republicans by running relatively conservative Democrats in potentially Republican constituencies. To win in those relatively conservative constituencies, those Democrats had to support gun rights. Forcing them now to vote for “gun control” could cause Democrats to loose the Senate in 2014, as many Democrats believe that supporting gun control caused them to do in 1994. (See Cameron Joseph 130117 “Vulnerable Senate Democrats balk at Obama’s gun control measures” at .

This vulnerability and ambivalence apply even – and particularly – to the Democratic leader of the senate, Harry Reid of Nevada. As a result, Reid has expressed skepticism about some of Obama’s gun proposals. He wishes to stick to the rule in Obama’s first term according to which Democrats do not use senate resources to pass a bill that can’t pass the House. Meanwhile, of course, House Republicans say they won’t bother to pass legislation that can’t pass the Senate! Also Alexander Bolton 130117 “Obama push on gun control puts Reid in tough political spot” at .)

Meanwhile, Obama still has majority public support for his main legislative proposals for gun reform. Universal background checks are overwhelmingly popular (88% approval), limiting ammunition magazines to 10 rounds substantially so (66% approval). Support for reinstating the ban on assault weapons and for stationing more police officers in schools is more modest (58% and 55% approval). The problem is, how to bring national average opinion to bear on legislators, particularly on legislators from districts where opinion departs from that average. Please see 2.2 below on Missing Movements. (Chris Cillizza and Scott Clement 130117 “President Obama has the public on his side on gun proposals” at .)

ACADEMIC ANALYSIS: POLITICS 2

This section asks to what extent political scientists have EXPLAINED anything about the policy politics surrounding guns. The first third of the section reprises the theme of how limited the regulation has been that the USA has achieved over gun violence. The middle third introduces a theme of “missing movements” that is fundamental not only to American gun politics but to current American politics as a whole. The last third of the section discusses the relevance to gun politics of a classic theme in American political science: that “policies make politics” and that different kinds of policies make different kinds of politics.

Limited regulation 2.1

This subsection elaborates slightly on the low “technical feasibility” of regulating gun violence in America. Regulation of guns can address (1) carrying, storage, and use (2) access by specific categories of “bad” persons (3) marketing and registration (4) types of “bad” guns and (5) severity of sentencing for violations of gun laws. Under the American division of authority between the national and subnational governments, historically most of these have fallen to states and localities to regulate. This devolution has its advantages: practical needs and community cultures differ drastically between, say, big metropolitan cities and small rural towns. However, this devolution has also produced inconsistent and lax regulation. Moreover, it makes the national government a tentative and indirect “interloper” in a policy domain in which post policy prerogatives are reserved to the states. (Vizzard 2000)

As noted above, the current national system for regulating gun transactions focuses on regularizing a PRIMARY MARKET for gun sales. Regulations require national licensing of all gun dealers and require those dealers to check the personal backgrounds of prospective gun buyers by consulting government data bases. The aim of the checks is to identify “bad” buyers such as convicted criminals, the mentally unstable, or the underage, who should be denied purchase. However, the existing regulatory regime has many defects. (On these defects see Vizzard 2000.)

First, even as regards primary markets, regulation does not provide a workable definition of “gun dealer.” Second, relevant databases on potential buyers remain incomplete. Third, the law does not require that data on transactions and equipment be compiled into a national database that would actually assist in enforcing regulations. (Proponents of gun rights fear that such a database would amount to a national registration system that, one day, might enable the national government to confiscate guns from all owners.) Fourth, current regulation allows a huge “loophole,” permitting sales at gun shows where background checks are not required. Gun shows are only a part of a large unregulated SECONDARY MARKET that accounts for 40%-50% of legal gun sales! Fifth, current regulation does not address the illegal TERTIARY MARKET of surreptitious sales by unlicensed sellers to unrecorded buyers..

Missing movements 2.2

American politics currently suffers from an absence of mass movements to push for LIBERAL “middle class” objectives, not just in gun politics, but in most other policy domains as well. The theme of “missing movements” is absolutely fundamental to the present and future of American politics, particularly from a progressive point of view. (For a journalistic account of “missing movements,” see Hedrick Smith 2012 Who Stole the American Dream? New York NY: Random House, 592 pages. Particularly Chapter Three “Middle-class power: How citizen action worked before the power shift,” 23-34 and Chapter Twenty-two “Politics: A grassroots response: Reviving the moderate center and middle-class power,” 410-426.)

Evidently Obama agrees, since he has just dispatched the director of his election campaign and other key staffers to lead grassroots mobilization BETWEEN elections to bring public pressure on congress to pass his programs. Organizing for Action will “play an active role” in “mobilizing around and speaking out in support of important legislation” during his second term.

Launching the organization in conjunction with his second inauguration, Obama wrote in an email to supporters:

“We may have started this as a longshot presidential primary campaign in 2007, but it’s always been about more than just winning an election. Together, we’ve made our communities stronger, we’ve fought for historic legislation, and we’ve brought more people than ever before into the political process. .... Organizing for Action will be a permanent commitment to this mission. We’ve got to keep working on growing the economy from the middle out, along with making meaningful progress on the issues we care about — immigration reform, climate change, balanced deficit reduction, reducing gun violence, and the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. .... I’m not going to be able to take them on without you.” (Quoted in Glenn Thrush and Reid J. Epstein and Byron Tau 130117 “Obama unveils 'Organizing for Action'” at .)

As regards guns, this section elaborates slightly on the low “political feasibility” of regulating gun violence in America. We begin by noting the skeptical analysis of criminologist William Vizzard, who noted that the liberal gun cause was a largely elite affair (2000). We continue by reporting the critical analysis of political scientist Kristin Goss, who explains that gun advocates have mobilized their mass base as an effective political force but gun critics have not. (Kristin A. Goss 2006. Disarmed : the missing movement for gun control in America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 282 pages.)

As this Guide has stressed throughout, the kinds of measures that American politics has succeeded in adopting to regulate guns have been more politically symbolic than practically effective (Shots in the dark, as William Vizzard calls them). Because of inadequate mobilization of mass support, in order to pass ANY control legislation, gun critics have had to make so many concessions to gun advocates that the resulting measures have been weak and inconsistent. Comprehensive regulation of all gun owners, gun transactions, and gun equipment has been politically impossible because it would mobilize too much opposition by too many stakeholders. So legislation has tried to define a few gun owners, sales, and equipment as “bad” in order to regulate only those, while allowing their more numerous “good” counterparts to remain unregulated. Such a narrowing is intended not only to minimize political opposition but also to maximize enforcement efficiency, by focusing enforcement on the most problematic persons. (Vizzard 2000.)

In effect elaborating the political side of Vizzard’s analysis, Goss’s 2006 book Disarmed analyzes the relative absence of a mass movement for gun control in America. She argues that advocates of gun RIGHTS have done the mass political work necessary to influence national legislation, while advocates of gun CONTROL have not. Conservative gun advocates “started local” and framed issues in a way that appealed to mass supporters. They proceeded incrementally and made small gains that rewarded those supporters. Liberal advocates of gun CONTROL pursued reforms at a national level and framed the issues in elite terms that did not connect with mass publics. They attempted large reforms and assumed it was obvious that their cause was morally compelling and therefore did not need ongoing small rewards to build mass support. This “rational national” strategy relied on the persuasiveness of good policies instead of the leverage of good politics. It was an inside strategy without an outside strategy, and it failed.

Vice-President Biden has indicated that, through Organizing for Action, the Obama administration plans to bring a vigorous “outside game” to bear on Washington gun politics (Thrush+ 130117).

Subsequently Goss has provided a similar explanation of the failure of women’s rights advocates to gain passage of an Equal Rights Amendment. (Kristin A. Goss 2012 The paradox of gender equality: how American women's groups gained and lost their public voice Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press, 256 pages.)

Policies make politics 2.3

One way to categorize policies is according to the pattern of politics that they tend to generate.

In other words, “policies make politics.” Famously, in 1964, the American political scientist Theodore Lowi posited that policies are either distributive, regulatory, or redistributive. On Lowi’s analysis, these different kinds of policies set up different patterns of interaction between politicians and publics and tend to be processed in different ways in different parts of American political institutions. (Lowi, Theodore J. 1964. "American business, public policy, case-studies, and political theory" World Politics 16,4 (October) 677-715. A revised version positing an additional “constitutive” type of policy is Theodore J. Lowi 1972 “Four systems of policy, politics, and choice, Public Administration Review 32, 4 (Jul-Aug) 298-310.)

DISTRIBUTIVE policies simply hand out short-term benefits to political clients without much attention to longterm costs (where the money is coming from). Both politicians and clients love such policies, which can be arranged rather privately between particular congressional subcommittees and particular political clients. From the beginning, distribution has been the staple of American politics. REGULATORY policies discipline some category of citizens (such as polluting industries) to benefit all citizens (who want a clean environment). Regulatory policies arose starting around 1900 largely to manage America’s suddenly industrialized economy. Processing regulatory politics requires more principled deliberation at higher levels within congress – major committees or a chamber as a whole. REDISTRIBUTIVE policies take from some citizens in order to give to other citizens. Classically this meant taking from the rich to give to the poor, as the 1930s New Deal and 1960s Great Society succeeded in doing for a while. Since then redistribution has increasingly been from the middle class to the rich. Redistributive policies tend to involve strenuous debate between large segments of society (capital versus labor, rich versus poor) and to involve the very highest levels of the political system, including the president.

Originally, Lowi treated mostly economic issues that politicians and publics process in an instrumental and calculative way. Lowi regards “social” issues as regulatory, since they involve imposing particular behaviors on individuals, ultimately by coercion. Later Lowi elaborated his framework to encompass the “moral” aspects of socio-cultural issues, the aspect that causes actors to process such issues in expressive and normative ways. (See his preface to successive editions of Raymond Tatelovich and Byron W. Daynes 2006 Moral controversies in American politics, 3rd edition Armonk NY: M. E. Sharpe, 292 pages.)

Lowi and his followers have classified the gun issue as such a “social regulatory” issue. Following Lowi’s 1964 ambitions, the editors of the relevant volume suggest a variety of patterns that “social regulatory” policies display, including where within American institutions they tend to be processed. Spitzer concludes that gun politics does indeed display most of those characteristics. (See both Spitzer’s chapter in the 2006 edition of the Tatelovich and Daynes volume and the 2012 edition of Spitzer’s own textbook on gun politics. The following is from Spitzer 2012, 16-17.)

Reordered, but in Spitzer’s words, these patterns are:

PRESIDENTIAL LEADERSHIP plays a relatively marginal role and operates primarily on the symbolic level.

CONGRESS is more heavily involved in this kind of issue than the president, but it tends to support the status quo, often following the lead of state legislatures instead of setting the course for the states.

The COURTS provide a key avenue for defining and changing the issue.

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCIES exercise limited control and jurisdiction over the issue, and political winds from Congress, the president and interest groups buffet these agencies.

FEDERALISM defines the structure and politics of the issue. That is, unlike many issues on which the federal government has become the primary actor, state and local governments continue to operate with a high degree of autonomy and control, even in the presence of federal regulations.

The POLITICAL PARTIES generally seek to exploit differences over social regulatory policy, with Republicans using such issues to mobilize conservatives and Democrats seeking to mobilize liberals.

SINGLE-ISSUE GROUPS are prevalent in the politics of the issue, and they behave in an absolutist, polarizing fashion; that is, they are singularly strident, they seek and defend extreme positions, and they are reluctant to compromise.

Rallying and mobilizing PUBLIC OPINION behind change is difficult; at the same time, for change to occur, it must be linked to and draw support from social/community norms and values.

Most of this remains true and insightful for current gun politics. Particularly noteworthy is that much of gun policy is set at the subnational level and that mobilizing public opinion behind significant policy change requires appealing to community values. Current gun politics do starkly contradict one item: Presidential leadership, far from being marginal and symbolic, has been central to placing guns squarely on the national policy agenda. Moreover, as reported above, the president himself has provided concrete proposals for action, following the recommendations of his vice-president and cabinet. Furthermore, recognizing that many of those proposals will be difficult to get through congress, Obama has taken some 23 concrete actions himself, using his executive powers.

More broadly, I am not happy with the “social regulation” classification of gun matters, either as a basically “moral” issue or as a purely regulatory one.

As to “moral,” it is certainly true that the Right has succeeded in defining guns as an Identity issue. But that definition is partisan and tendentious, intended to supercede the fact that regulating guns should be primarily a Security issue of public safety and public health. Moreover, the Right’s definition is also intended to obscure the fact that guns are also, to some extent, an Economic issue: again, guns should be subject to regulation for public health and safety just like any other commondity.

As to “regulatory,” certainly th egun issue is regulatory, but it also has distributive and redistributive aspects – not only in the moral aspect, but in their security and economic aspects as well. For example, in the gun case, even the Identity aspect is quite redistributive: conservatives fear that progressives are taking the identity of America away from them and “redistributing” it to progressives. The Security aspect is also quite redistributive: Gun advocates became so insistent in the 1970s because they feared that inner-city blacks were arming themselves, redistributing security away from whites to blacks (who of course saw it the other way around). Moreover, gun advocates now fear that gun opponents want to take their security away from Them and redistribute it to Others. The Economic aspect of gun politics, in addition to the regulatory pattern posited above, may even have some minor distributive patterns (protecting domestic gun manufacturers from foreign competition and protecting local employers from nationally-imposed costs.)

ACADEMIC ANALYSIS: FRAMINGS 3

From the point of view of societal function, there are three main types of issues: SECURITY versus ECONOMY versus IDENTITY. It is certainly true that, since the outbreak of “culture war” in the 1970s, American politics has processed guns as an ideologically polarized “moral” or IDENTITY issue, as mainstream American political science now treats it. However, guns differ from other moral issues in that guns themselves are not an intrinsically moral matter like abortion or gay marriage. Before the 1970s guns were at least partly an ECONOMIC issue: gun lobbies helped craft various economically protectionist measures to assist the gun industry and even token gun controls to preempt more drastic controls. Before THAT guns were largely a SECURITY issue: from the beginning of the colonial period, settlers used guns as weapons against Native Americans, during the Revolutionary period they used guns as weapons against the British and, from the beginning of the Republic, whites made sure that blacks did not have guns.

Security 3.1

Thus, in the first instance, arguably the gun domain centers on Order functions and poses a SECURITY issue with a “security logic” of threat and fear. Indeed, Spitzer’s textbook, which begins by treating guns as a moral issue, ends up by arguing that their basic dynamic is a “security dilemma” in which insecurity leads to defensive measures that further heighten insecurity, and so on. In politics, perhaps a variant of that is the dynamic according to which defenders of gun rights view ANY regulation of guns as a step toward their ultimate nightmare of total Confiscation and Prohibition. The main analysis by a security professional (Vizzard 2000) identifies two contending “frames” in gun politics that I would place in the “security sector,” at the micro-individual and macro-political levels, respectively. (Vizzard identifies other frames that, below, I place in other sectors, also at either micro or macro levels.)

The frame used by most Americans is the micro-security CRIME CONTROL FRAME elaborated by professional criminologists and practiced by police, clearly a security issue. Putting guns in that frame usually suggests that guns facilitate crimes by individuals and therefore should be controlled to protect other individuals – including police themselves, who strongly advocate gun control. Nevertheless, within the crime control frame, opponents of gun control are emphatic that “guns don’t commit crimes, people do.” The actual relationship between guns and crime, and between actual crime rates and public fear of crime, involves many fraught questions. For example, conspicuous increase in crime raises public fears, but even rather significant DECREASE in crime does not necessarily REDUCE fears (as the large fall in crime in the late 1990s did not).

Overall, social science research hotly disputes the relationships between level of guns and level of violent crime. Some even argue that the relationship is actually inverse (John R. Lott 1998 More guns, less crime : understanding crime and gun-control laws. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 225 pages). Here “more guns” refers to variation across American counties in the permissibility of carrying guns. (On Lott’s claims see Glenn Kessler 121217 “Do concealed-weapon laws result in less crime?” at )

This controversial research remains currently relevant because even some commentators who are not committed advocates of gun rights are now wondering whether, given the inability of government to protect citizens from guns, government should allow citizens to use guns to protect themselves. (For example, Jeffrey Goldberg 1212 “The case for more guns (and more gun control)” at .) This is a standard argument of NRA, repeated at the end of this week by its head: “The only thing that protects against a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” So he recommended more guns: An armed policeman in every school in America! But NOT control of guns themselves! From this point of view, the preference of most schools to be “gun free zones” is simply irresponsible and actually reprehensible! (For the skeptical reaction of an opponent of the gun control response to a previous gun tragedy, see Jacob Sullum 120725 “Outrage is not an argument: Politicians should resist demands to do something about guns in response to the Aurora massacre” at .)

Other social scientists have found methodological faults with research purporting to prove the protective benefits of guns and themselves done research that has reached opposite conclusions. These disagreements are often technical ones that this author cannot evaluate. In any case, the conventional wisdom now purveyed by mainstream media is that having a gun is more likely to result in injury than in protection. For example, the mother of the Newtown shooter legally owned guns, and those were what enabled her son to kill her and others. (The chapter in Wilson 2007 on “Statistics and firearms” provides a fair assessment of research claims about the costs and benefits of guns in causing or preventing violence.)

At the “macro-security” level is the SOVEREIGNTY/RIGHTS FRAME. Again, this can be used to argue either for or against gun control. Proponents of gun control COULD use the SOVEREIGNTY side of that frame to argue in favor of gun control: the most basic responsibility of a modern state is to maintain a monopoly of coercion within its jurisdiction and thereby guarantee law and order to its citizens. To achieve that, a state must control guns. That is the usual position in Western countries. Nevertheless, in America, politicians seldom emphasis that argument, because it implies exactly what gun lovers most fear, that the government will confiscate their guns. Meanwhile, opponents of gun control use the RIGHTS side of the sovereignty/rights frame to argue that gun control violates American tradition: in rebelling against the British, Americans established the principle that citizens need guns in order to defend themselves against “tyranny.” From the sovereignty side, two anti-gun lawyers have recently examined this pro-gun contention, arguing that – as one might expect! – gun rights “insurrectionism” is incompatible with democracy (Joshua Horwitz and Casey Anderson 2009Guns, democracy and the insurrectionist idea. Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press, 274 pages.)

Identity 3.2

Guns can also become an IDENTITY issue, part of the “culture wars” between America’s liberal coasts and its conservative interior, and part of the accompanying partisan wars between Democrats and Republicans. Vizzard recognizes both of these wars in two of his other frames through which American politics views gun issues: his micro-individual CULTURE FRAME and macro-partisan SYMBOLIC FRAME. Identity can explain better than Security why gun advocates are so adamant about not allowing restrictions on guns. Moreover, as noted under BACKGROUND, both the regional-cultural divisions and their correspondence to partisan alignments are confirmed by Pew polls. Since neither side will subside, latitude for tightening restrictions on guns is likely to remain small. Most characterizations of gun affairs as a moral issue blame ideological moralization for political polarization, implying the desirability of more empirical approaches. However, a few authors make the opposite point: Gun affairs DO involve significant moral disagreements that actually can be obscured by purely causal analysis. Such principled disagreements can be resolved only through constructive moral debate. (See for example Christopher Eisgruber in Harcourt ed. 2003.)

Guns are to some extent also an ECONOMIC issue. Certainly gun companies and gun dealers want to make money, and of course their desire to sell as many guns as possible contributes to the gun problem. Some “gun control” measures may have been introduced less to protect the public from guns and more to protect domestic manufacturers from foreign competition. Protectors of the gun industry may even have introduced lax regulations in order to preempt more stringent ones. Moreover, the industry has been able to forestall regulation of many products that constitute hazards to public “health and safety,” as increasing liability suits against gun companies claim In 2005 the gun industry even almost obtained national legislation protecting it from such suits! One might think that the leading gun interest lobbying group, the National Rifle Association, is simply a “front” for the industry and largely funded by it. It is true that the NRA and the industry cooperate closely, and that the industry does contribute to NRA. But in fact the NRA is funded mostly by many small contributions from its many committed members, and its main asset is actually not its money, but its ability to mobilize so many members to vote one way or another in elections.

Economy 3.3

Another sense in which guns can be regarded as having an “economic” logic is Vizzard’s PUBLIC HEALTH FRAME. As he says, the logic of that frame is antithetical to the sovereignty frame: “instead of law and rights... the language of utility, risk, and social costs.” (9). So perhaps guns can be analyzed as an ordinary economic issue after all. Nevertheless, few other Economic products produce such spectacular tragedies, after which most other products are regulated. Arguably only the Security – and particularly the Identity – aspects of the gun issue fully explain the difficulty of getting gun issues onto the political agenda.

(For criticism of the gun industry see Tom Diaz 1999 Making a killing: The business of guns in America. New York NY: The New Press, 258 pages. For an update on the trend toward marketing increasingly lethal weapons to civilians, in order to generate new sales, see Tom Diaz 2013 (June) The last gun: Changes in the gun industry are killing Americans and what it will take to stop it. New York NY: The New Press, 224 pages. For reaction against the gun industry immediately after Newtown, see Brad Plumer and David A. Fahrenthold 121218 “Gun industry recoils from horror” at . On liability suits, see Timothy D. Lyton ed. 2005Suing the gun industry: A battle at the crossroads of gun control & mass torts. Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press, 418 pages.)

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号